Spoiler: Probably not.

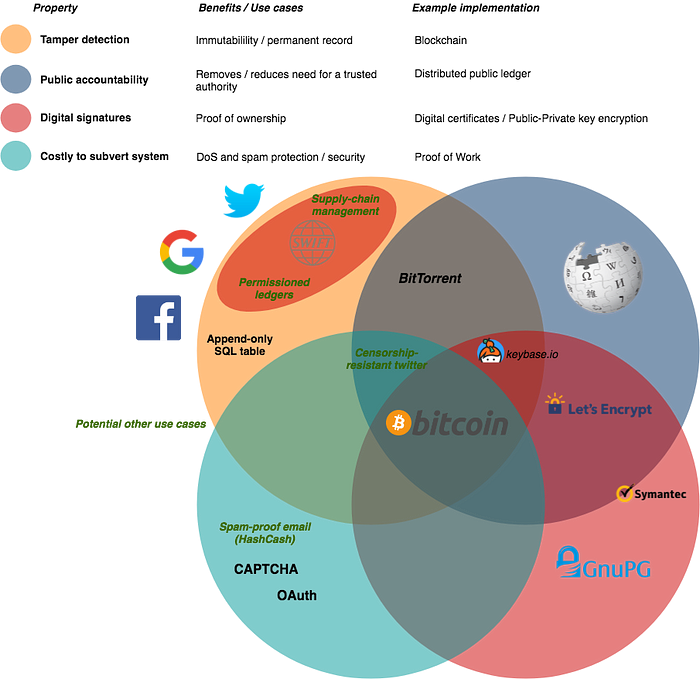

In Part I of this article, we looked at the four fundamental features of self-sovereign uncensorable money: tamper-evident records, public accountability, proof-of-ownership and corruption resistance.

Bitcoin has these features through its four key enabling technologies: a block chain, a distributed public ledger, digital signatures and proof-of-work.

In this article, we’ll use these four features as a checklist to determine whether some of the most loudly touted use-cases of Blockchain really need one.

Banking

First, the banks.

Here’s a random sampling of the many headlines that have been splashed across finance rags’ front pages in the last few years:

National Bank of Egypt Joins 200 Financial Institutions in the ‘R3 Blockchain Alliance’

Blockchain could slash investment banks’ costs by 30%

R3, UK regulator and banks team up on blockchain-based mortgage reporting

and my personal favourite:

We Don’t Need Blockchain: R3 Consortium After $59 Million Research

Given that by Blockchain¹, banks really mean “the technology that underlies Bitcoin”, let’s take a look at which of the four features of Bitcoin a bank is really after when it comes to settling interbank transfers.

Bitcoin was conceived as trustless money and designed to remain operating in the most adversarial conditions imaginable.

With banks, we have a fairly small community that is heavily regulated, and that do actually trust each other to some degree. Already, the case for using Blockchain is looking questionable. That said, the sheer amount of money that passes between the banks makes the cost of any breach of trust incredibly high.

Clearly tamper detection of the transaction history is a must-have here. But is a block chain the correct data structure to achieve it? I might be convinced that a chain of digital fingerprints would be useful, but these could very easily stored in a SQL database rather than a linear chain of transactions; particularly if you’re dealing with millions of transactions a day. But tamper-detection: definitely.

What about digital signatures and proof of ownership? Without a doubt. Multiple signatures. The more the merrier I would think.

Awesome, we’re getting there. So now we add Public Accountability from distributed public records.

Yeah, public accountability has never been the banking sector’s strong suit. So let’s scratch that one.

That leaves Proof of Work. Well, if you think about it for a while, you’ll realise that Proof of Work isn’t all that useful if you don’t also have a public ledger.

Remember that Proof of Work makes it expensive to corrupt a system in a decentralised and random way (See Part I). If your system is private or semi-private, it’s not decentralised and you can rely on traditional (and cheaper) methods to do this.

Centralisation has its benefits. Good old firewalls, air-gapped servers, multiple redundant automated backups and so on will achieve your goals without having to consume the entire output of the Grand Coulee dam².

So that means that the Banks’ ideal “Blockchain” is just tamper detection plus digital signatures. This setup has been dubbed “permissioned ledgers”. To me, this sounds like a fancy name for a bunch of databases that have tightly controlled access along with strong cryptographic signatures. A good example of a permissioned ledger is SWIFT, the current interbank settlement system.

Ultimately when banks say they want “Blockchain to dramatically reduce interbank settlement costs” what they’re really saying is that they want more competition for SWIFT to help drive down the dominant player’s monopolistic pricing.

Do banks need a blockchain? Nah³.

[1] For the rest of this article, I’m going to use Blockchain (with a capital B) in the sense that is implied by MSM, i.e. a distributed public ledger with a proof of [work/stake/alpaca] consensus algorithm.

[2] Of course this opens up a secondary debate on centralised vs. decentralised security. The fact is that every technical decision involves trade-offs, so let’s just leave that alone for now.

[3] I guess I’ve just lost out on all those sweet speaker fees at Blockchain4Banks conferences :(

Supply-chain management

Blockchain technology is going to revolutionise the supply-chain management (SCM) industry. According to the headlines. BHP Billiton was one of the first large companies to announce in 2016 that they were implementing Blockchain for their core sample supply chain. Similar stories were doing the rounds about the diamond industry in April 2018.

The business of inventory procurement and tracking is a bloodthirsty wasteland of backstabbing, double-dealing and theft. Ok, I don’t know if it is, but it sounds that way given the way that the SCM industry paints themselves just before the announcement that “Blockchain” will fix all this.

So let’s look at supply chains through the lens of the 4 features of Bitcoin. Let’s assume for the moment that there really is no trust between parties in the supply chain and everyone is convinced that the guy above them in the chain is ripping them off while simultaneously cheating their customers out of everything they have.

Would this industry benefit from tamper-detection records? Yes, I believe so.

What about digital signatures? Yes, this would be useful too.

Now what about public accountability and proof of work? Hmm, I think we’ll find that the SCM players are with the banks on this one.

So again, it looks like “Blockchain” isn’t the answer for SCM, but permissioned ledgers might just do the trick.

However, the SCM industry has an additional hurdle to clear that the banks don’t have to worry about: How can blockchains find out about the real world in a reliable and trustless way? This is called The Oracle problem. You see, blockchains and permissioned ledgers are brilliant at letting you know when data in the system has been compromised. But they have zero sense whether that data is true or not.

In Bitcoin, the truth is defined as anything that exists on 50% or more of the ledgers. That’s not good enough for SCM. If a supplier inserts a record on the blockchain that his product is 98% pure, how do we know whether that statement is accurate or not? He could easily be faking his analysis report¹.

So maybe we require that another lab independently perform an analysis and publish their results to the blockchain. And then everyone can compare the two results. But it might be cheaper for the manufacturer (which just happens to be named Charlie’s Purest Products Inc.) to pay off the “independent” lab than improve their production quality.

Ok, so we require a third lab, and a fourth. Then a fifth. At some point all we’re doing is building a bitcoin-like consensus system for assay labs. But unlike bitcoin transactions that can be shared around the world in seconds, we need to ship samples of product around the world to labs so that they can do their verification tests. But how do we manage the logistics of this process and keep it safe? Maybe we could use some sort of blockchain-based SCM system…

The Oracle problem presents a major barrier for any industry that wants to connect the real world to the world of Blockchain accounting. One might say that it’s the Holy Grail of Blockchain, because if it is solved, then several really interesting applications open up, but right now it feels insurmountable. But I hold out hope: Firstly, to my knowledge, the Oracle problem has not been proven to be unsolvable for any of the cases we’re interested in. Secondly, we do have at least one trustless working oracle today: Bitcoin’s Proof of Work algorithm. The proof of work hash is a statement that a miner has spent a predetermined amount of money (on average) to produce that block. It’s linking real-world information (energy consumption) to the blockchain and doing so in a trustless way.

The Oracle Problem will likely be “solved” for information-only problems first. This is a qualified statement, because most proposed solutions are not strictly trustless, but diffuse or spread the trust around to an “acceptable” level. Maybe this pragmatic approach is good enough. Still, the challenges are significant, if the slow progress of the Augur Project is any indication.

Providing secure providence guarantees for physical goods is several orders of magnitude more difficult.

Verdict: Usually not, and you have the Oracle Problem

[1] I worked for an oil company for 12 years. We would occasionally find labs would fake internal analyses because some guy’s performance bonus relied on some KPI that required him to deliver x number of assay reports a day within a certain variance. Which he duly delivered. He hadn’t done the actual assays but the reports met the KPI. That’s one little lab on one refinery. Let’s just say that the problem of achieving data integrity on a large scale is.. non-trivial.

Government spending auditing

The auditing industry might have been sweating bullets at the thought that the blockchain would end a $160 bn per year industry. Auditing on a public blockchain is undesirable for the same reason that the banks and supply-chain industries don’t like it. Self-auditing blockchains also suffer from the Oracle problem.

But what about Public spending? Whereas companies don’t want their financial dealings exposed to public scrutiny, what your Government does with your taxes is a matter of public interest.

This is a promising use case. Tamper proof, public records of public spending would increase accountability and reduce graft in public offices — if we can also solve the Oracle Problem (and as we discussed above, that’s one helluva big if). A suitable proof of work mechanism should make it too expensive for government cronies to cheat the system while “miners” get rewarded in someway for verifying that funds were spent were they were claimed to be.

Implementing this is a tough sell — “Hey guys, we want you to vote this thing into law that slashes your retirement fund by 90%. Sound good? Great!”

Verdict: This one might just work, but unlikely to happen in our lifetimes. And you know, the Oracle Problem.

Identity

You want to bet on England winning the 2018 World Cup¹. You sign onto RandomSportsBets, (rsb.com). But before you can place your bet, you have to go though this standard age verification process :

- You hand over a ton of personal information.

- rsb.com stores and sends this information to verify your identity with some third party company.

- If you meet the age requirement (the only thing they really care about), you can deposit and place your bet.

- rsb.com gets hacked and all your data is sold on the black market.

Blockchain folks get really excited by this. I mean, solving the identity problem, not buying your personal data on the dark web.

Here’s the plan: First you stick your identity stuff on the blockchain. Then you produce digital certificates for whatever claims you want to make (e.g. I’m over 18) and reveal nothing else.

On the face of it, this is pretty compelling, but do we need Blockchain?

Consider that Coinbase has 13M+ customers, the majority of whom have gone through Coinbase’s KYC/AML sign-up process. Coinbase doesn’t run a block chain. But they could pretty easily provide a service that does exactly what we’re describing: User’s log into the Coinbase Identity App, select the info that they want certified (age > 18), and then the receive a QR code that acts as a digital certificate co-signed by Coinbase and yourself attesting to the truth of the information selected.

rsb.com could accept that certificate knowing that a) the client says they’re over 18 and b) Coinbase backs up that claim.

There’s no need for tamper-proof logs, public ledgers or proof of work.

But this model has risks. Given that Coinbase is a centralised service, they do serve as a single point of failure. Coinbase’s security model is world-class — military-grade or better — and their servers have never been hacked, but centralised information sources are magnets for hackers. And governments. The strongest firewalls in the world can evaporate under the plasma-like glare of a subpoena.

Maybe the cost of a proof-of-work blockchain is worth paying to secure all of our Personal Information on a distributed, uncensorable, un-subpoena-able database. Maybe. I’m not 100% sure about this, but it is an argument that’s worth making. And the one that guys like Civic are banking on.

Verdict: Maybe. I’m not 100% convinced. Perhaps there’s space for both.

[1] Because you hate money².

[2] This might not age well :)

Public research

Academics make their careers out of publishing research. Editors and publishers of scientific journals love printing articles, but only if it increases the readership and prestige of their publications. This situation leads to a set of incentives that aren’t entirely aligned with what the scientific process purports to achieve: The rigorous and objective pursuit of Truth¹.

What we end up with are a set of publication biases:

- Journals overwhelmingly prefer studies with positive results rather than negative ones (we found X to have an effect on Y vs. we found that X has no effect on Y).

- Knowing this, academics, when faced with results that don’t support their hypothesis are tempted to cherry pick, or re-interpret their data to get the result they were looking for.

What if we change how research is done, particularly public research, and publicly funded medical clinical trials in particular:

- The researcher writes up his hypothesis and experimental plan, including how the data will be used in statistical inferences (The Plan).

- He then publishes a timestamped, digitally-signed hash of the Plan on a distributed public ledger.

- He then carries out the experiment. The experimental data is also signed and hashed and the hash published to the blockchain.

- Now cherry picking is impossible since the researcher has publicly committed to his process ahead of time.

This scheme has several drawbacks, but let’s assume for the moment that it works as advertised.

What we’d immediately notice is a dramatic fall in positive results from experimental studies. But the integrity of research would be vastly improved to the long-term benefit of everyone (especially researchers; once publishers become accustomed to the new normal of 50% — 80% studies with negative results, they should become more inclined to publish those articles).

This system requires the following properties:

- Tamper-evident logs via a block chain

- Public scrutiny via a distributed public ledger

- Digital signatures

And because we’re using a distributed public ledger, then some sort of sybil-attack resistance is required; typically via a proof of work system.

So this feels like a valid use case for Blockchain technology.

I mentioned that this scheme has drawbacks. As stated this idea is pretty naiive and essentially, it boils down to the Oracle problem again. The system could fairly easily be gamed: Unethical researchers could do their experiments first, cherry-pick, and then commit their experimental plans and data.

However, this isn’t that different to how research is gamed today. And Academia already has a system for dealing with cheaters: reputation. University careers aren’t known for their fat pay checks. So we might reasonably assume that academics are more interested in renown than money (and the belief that one usually leads to the other). Cheating in research is very risky because the cost of being caught is absolutely catastrophic — your career will be ruined.

So perhaps this is one way to try and work around the Oracle problem in this instance: We don’t even try and eliminate cheating, but construct the game theory incentives in such a way that it’s not in researchers interest to try and cheat; the costs of being caught are just to high².

[1] Philosophy majors: Hold your horses. Objectivity and Truth (with a capital T) may not exist, but I think you get my overall point.

[2] In fact, this is almost exactly how Augur is structuring its prediction market Oracles. It’s also no coincidence that the Augur token is called REPutation.

Verdict: Compelling, but some work to do to prevent cheating.

tl;dr

There’s a lot of hype around Blockchain technology. I’ve presented a straightforward framework that identifies the four fundamental features of what makes Bitcoin a revolutionary technology: tamper-evident logs (the block chain), cryptographic proof of ownership (digital signatures), public accountability (the distributed public ledger) and corruption resistance (proof of work).

If we use these four features as a checklist, we can evaluate any proposed use case of Blockchain technology and decide whether the potential is genuine, or whether it’s just buzzword bingo.

In this article, we looked at some of these proposed use cases for Blockchain. It was a far from exhaustive — a mere soupçon of some cases that I find interesting:

- The R3 foundation spent tens of millions of dollars evaluating Blockchain for banks. Ultimately they decided that it wasn’t necessary. If they had consulted this article series, they would have realised that within minutes, and I would have saved them millions of dollars.

- Supply-chain management has a slightly more legitimate use case, but I doubt that the industry would love having their business put in a public ledger. They also have a serious barrier in the Oracle problem — reliably adding real-world data to the blockchain.

- Areas of public interest are a very interesting use case for Blockchain technology. We looked at government spending auditing and scientific research pre-commitments. Both have adoption hurdles (to put it mildly), not least of which is the Oracle Problem.

Ultimately, the future of Blockchain applications (beyond money) lies in whether the benefits of having a decentralised, public record secured by proof-of-work outweighs its costs. None of these applications are going to be win-win, but will necessarily involve trade-offs.

Finally, given that the Oracle Problem plays such a huge role in many of the more interesting applications, we will need to understand this better. Perhaps the Oracle Problem isn’t really solvable (in a formal sense), but can be mitigated by moving the centre of gravity of trust in a more palatable way for users of the system.