Table of Contents

- Introduction

- I2P Network

- Tor Network

- Differences between I2P and Tor

- Conclusion

- References

- Appendices

- Contributors

Introduction

Invisible Internet Project (I2P), Tor and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are well-known anonymity networks. They are all designed in different ways and for specific uses, although most people use them with the intent of privately browsing the Internet. These network functions have very similar characteristics, but also have important differentiators in how they work to anonymize and secure users’ Internet traffic.

In this report we’ll examine what Tor and the I2P networks are, the paradigms of how they work, their security infrastructure and their potential or known use-cases in the blockchain domain.

I2P Network

What is I2P?

I2P (known as the Invisible Internet Project - founded in 2003) is a low-latency network layer that runs on a distributed network of computers across the globe. It is primarily built into applications such as email, Internet Relay Chat (IRC) and file sharing [6]. I2P works by automatically making each client in the network a node, through which data and traffic are routed. These nodes are responsible for providing encrypted, one-way connections to and from other computers within the network.

How does I2P Work?

I2P is an enclosed network that runs within the Internet infrastructure (referred to as the clearnet in this paradigm). Unlike VPNs and Tor, which are inherently “outproxy” networks designed for anonymous and private communication with the Internet, I2P is designed as a peer-to-peer network. This means it has very little to no communication with the Internet. It also means each node in I2P is not identified with an Internet Protocol (IP) address, but with a cryptographic identifier ([1], [2]). A node in the I2P network can be either a server that hosts a darknet service (similar to a website on the Internet), or a client who accesses the servers and services hosted by other nodes [6]. Tor, on the other hand, works by using a group of volunteer-operated relay servers/nodes that allow people to privately and securely access the Internet. This means people can choose to volunteer as a relay node in the network and hence donate bandwidth [13]. Compared to Tor, each client/server in I2P is automatically a relay node. Whether data is routed through a specific node is normally bandwidth dependent.

Since there is no Internet in I2P, the network is made up of its own anonymous and hidden sites, called eepsites. These exist only within the network and are only accessible to people using I2P. Services such as I2PTunnel, which use a standard web server, can be used to create such sites.

I2P Infrastructure

Routing Infrastructure and Anonymity

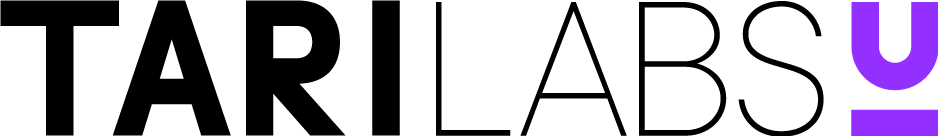

I2P works by installing an I2P routing service within a client’s device. This router creates temporary, encrypted, one-way connections with I2P routers on other devices. Connections are referred to as one way because they are made up of an Outbound Tunnel and an Inbound Tunnel. During any communication, data leaves the client’s devices via the outbound tunnels and is received on other devices through their inbound tunnels. This means that messages do not travel in two directions within the same tunnel. Therefore, a single round-trip request message and its response between two parties needs four tunnels [4], as shown in Figure 1. Messages sent from one device do not travel directly to the inbound tunnel of the destination device. Instead, the outbound router queries a distributed network database for the corresponding address of the inbound router. This database is comprised of a custom Kademlia-style Distributed Hash Table (DHT) that contains the router information and destination information. For each application or client, the I2P router keeps a pool of tunnel pairs. Exploratory tunnels for interactions with the network database are shared among all users of a router. If a tunnel in the pool is about to expire or if the tunnel is no longer usable, the router creates a new tunnel and adds it to the pool. It is important to recall later that tunnels periodically expire every 10 minutes, and thus need to be refreshed frequently. This is one of I2P’s security measures that are performed to prevent long-lived tunnels from becoming a threat to anonymity [3].

Figure 1: Network Topology [6]

Distributed Network Database

The Network Database (NetDB) is implemented as a DHT and is propagated via nodes known as floodfill routers using the Kademlia protocol. The NetDB is one of the characteristics that make I2P decentralized. To start participating in the network, a router installs a part of the NetDB. Obtaining the partial NetDB is called bootstrapping and happens by ‘reseeding’ the router. By default, a router will reseed the first time by querying some bootstrapped domain names. When a router successfully establishes a connection to one of these domains, a Transport Layer Security (TLS) connection is set up through which the router downloads a signed partial copy of the NetDB. Once the router can reach at least one other participant in the network, the router will query for other parts of the NetDB it does not have itself [12].

The NetDB stores two types of data:

-

RouterInfo.

When a message is leaving one router, it needs to know some key pieces of data (known as RouterInfo) about the

other router. The destination RouterInfo is stored in the NetDB with the router’s identity as the key. To request a

resource (or RouterInfo), a client requests the desired key from the node considered to be closest to the key. If

the piece of data is located at the node, it is returned to the client. Otherwise, the node uses its local knowledge

of participating nodes and returns the node it considers to be nearest to the key [3]. The RouterInfo in the NetDB

is made up of ([4], [6]):

- The router’s identity - an encryption key, a signing key and a certificate.

- The contact addresses at which it can be reached - protocol, IP and port.

- When this was created or published.

- Options - a set of arbitrary text options, e.g. bandwidth of router.

- The signature of the above, generated by the identity’s signing key.

-

LeaseSets.

The LeaseSet specifies a tunnel entry point to reach an endpoint. This specifies the routers that can directly

contact the desired destination. It contains the following data:

- Tunnel gateway router - given by specifying its identity.

- Tunnel ID - tunnel used to send messages.

- Tunnel expiration - when the tunnel will expire.

- Destination itself - similar to router identity.

- Signature - used to verify the LeaseSet.

Floodfill Routers

Special routers, referred to as floodfill routers, are responsible for storing the NetDB. Participation in the floodfill pool can be automatic or manual. Automatic participation occurs whenever the number of floodfill routers drops below a certain threshold, which is currently 6% of all nodes in the network ([6], [7]). When this happens, a node is selected to participate as a floodfill router based on criteria such as uptime and bandwidth. It should be noted that approximately 95% of floodfill routers are automatic [8]. The NetDB is stored in a DHT format within the floodfill routers. A resource is requested from the floodfill router considered to be closest to that key. To have a higher success rate on a lookup, the client is able to iteratively look up the key. This means that the lookup continues with the next-closest peer should the initial lookup request fail.

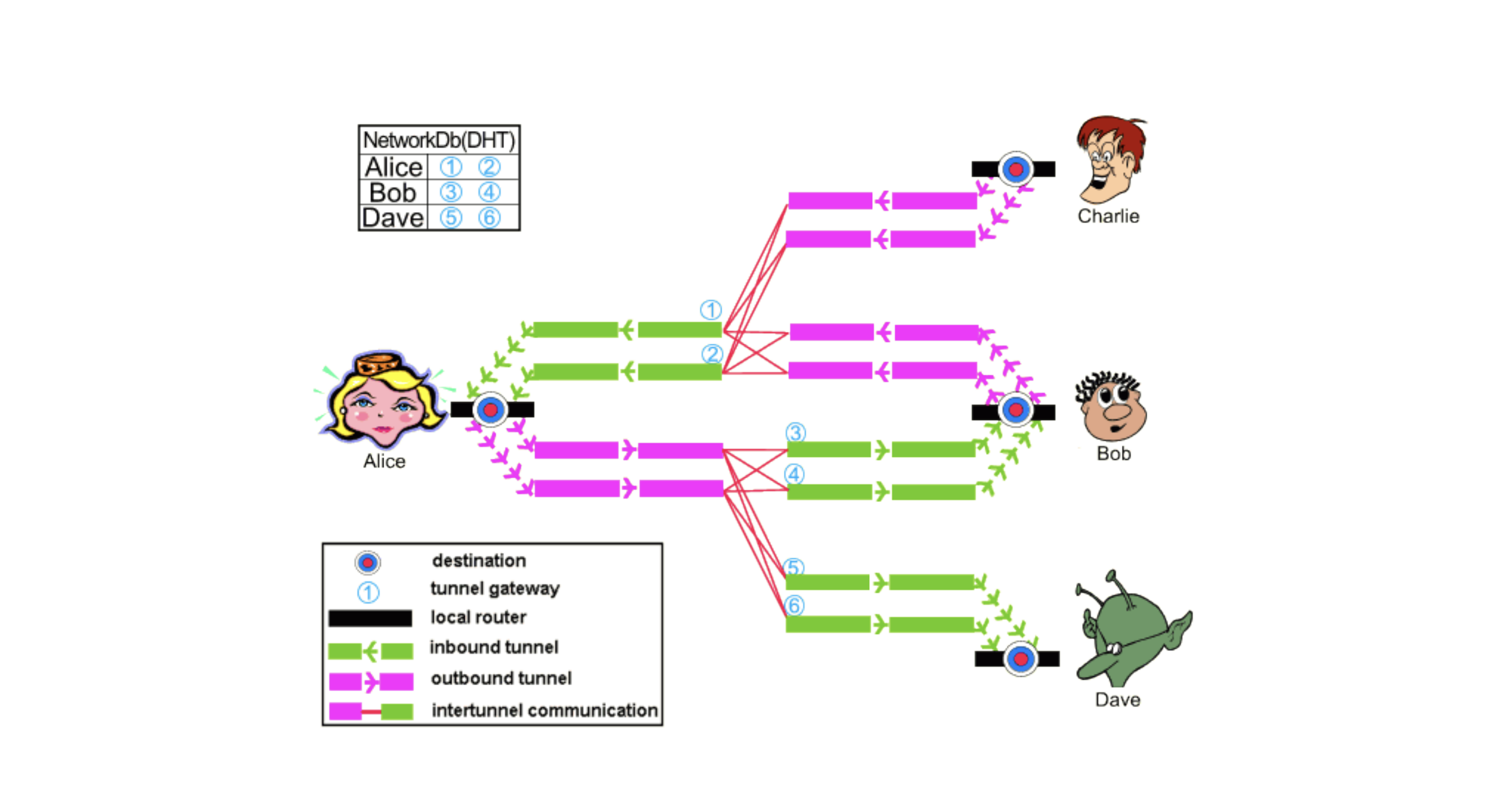

Garlic Routing

Garlic routing is a way of building paths or tunnels through which messages in the I2P network travel. When a message leaves the application or client, it is encrypted to the recipient’s public key. The encrypted message is then encrypted with instructions specifying the next hop. The message travels in this way through each hop until it reaches the recipient. During the transportation of the message, it is bundled with other messages. This means that any message travelling in the network could contain a number of other messages bundled with it. In essence, garlic routing does two things:

- provides layered encryption; and

- bundles multiple messages together.

Figure 2 illustrates the end-to-end message bundling:

I2P Threats, Security and Vulnerability

The I2P project has no specific threat model, but rather talks about common attacks and existing defenses. Overall, the design of I2P is motivated by threats similar to those addressed by Tor: the attacker can observe traffic locally, but not all traffic flowing through the network; and the integrity of all cryptographic primitives is assumed. Furthermore, an attacker is only allowed to control a limited number of peers in the network (the website talks about not more than 20% of nodes participating in the NetDB and a similar percentage of the total number of nodes controlled by the malicious entity). In this section, we’ll look at different threat models affecting the network [3].

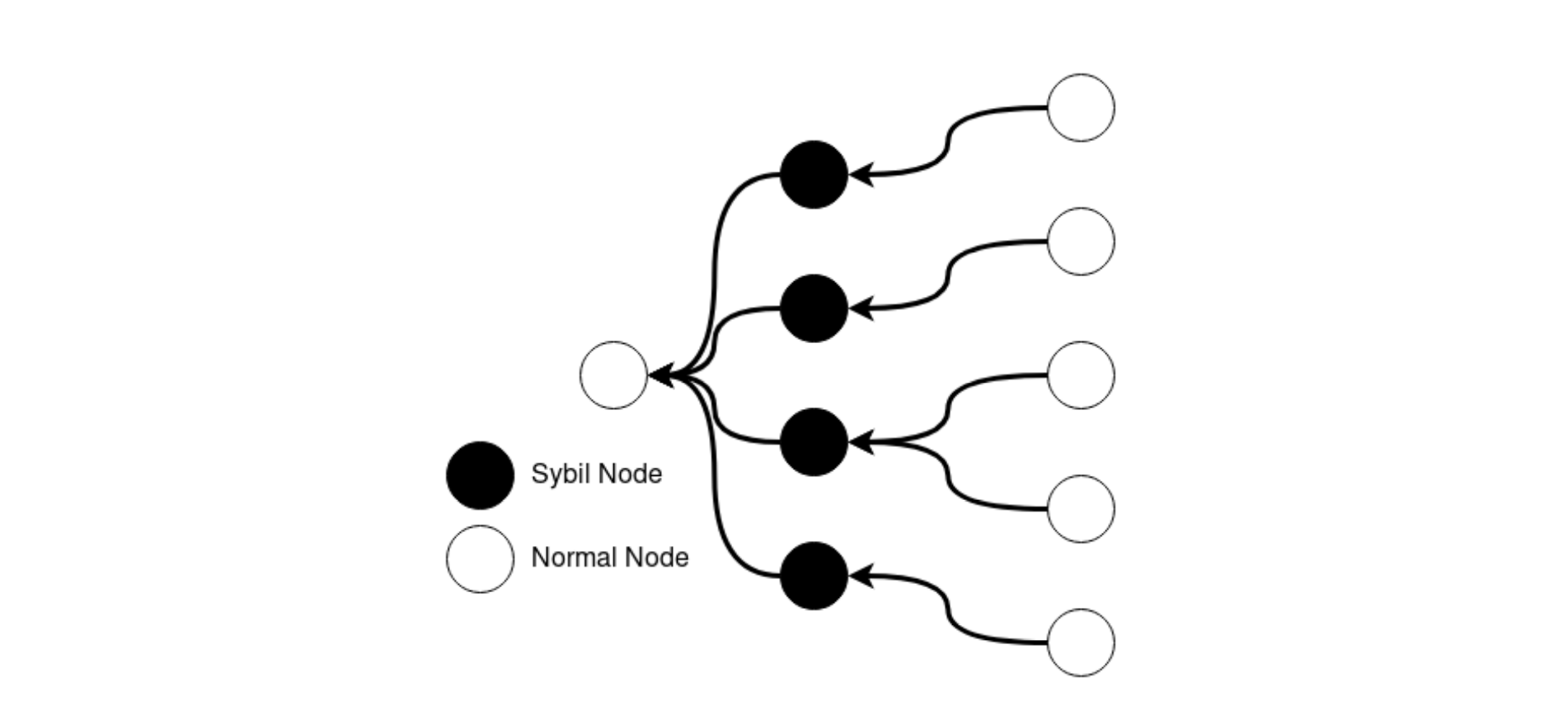

Sybil Attacks

The Sybil attack, illustrated in Figure 3, is a well-known anonymity system attack in which the malicious user creates multiple identities in an effort to increase control over the network. Running this attack over the I2P network is rather difficult. This is because participants/clients in the network evaluate the performance of peers when selecting peers to interact with, instead of using a random sample. Since running multiple identities on the same host affects the performance of each of those instances, the number of additional identities running in parallel is effectively limited by the need to provide each of them with enough resources to be considered as peers. This means that the malicious user will need substantial resources to create multiple identities.

Figure 3: Sybil Attack [5]

Eclipse Attacks

In eclipse attacks, a set of malicious and colluding nodes arranges that a good node can only communicate with malicious nodes. The union of malicious nodes therefore fools the good node into writing its addresses into neighbouring lists of good nodes. In a Sybil attack, a single malicious node has a large number of identities in the network in order to control some part of the network. If an attacker wants to continue a Sybil attack into an eclipse attack, the attacker will try to place malicious nodes in the strategic routing path in such a way that all traffic will pass through the attacker’s node [8].

Brute Force Attacks

Brute force attacks on the I2P network can be mounted by actively watching the network’s messages as they pass between all of the nodes and attempting to correlate messages and their routes. Since all peers in the network are frequently sending messages, this attack is trivial. The attacker can send out large amounts of data (more than 2GB), observe all the nodes and narrow down those that routed the message. Transmission of a large chunk of data is necessary because inter-router communication is encrypted and streamed, i.e. 1,024 byte data is indistinguishable from 2,048 byte data. Mounting this attack is, however, very difficult and one would need to be an Internet Service Provider (ISP) or government entity in order to observe a large chunk of the network.

Intersection Attacks

Intersection attacks involve observing the network and node churns over time. In order to narrow down specific targets, when a message is transferred through the network, the peers that are online are intersected. It is theoretically possible to mount this attack if the network is small, but impractical with a larger network.

Denial of Service Attacks

Denial of service attacks include the following:

Greedy User Attack

A greedy user attack occurs when a user is consuming significantly more resources than they are willing to contribute. I2P has strong defenses against these attacks, as users within the network are routers by default and hence contribute to the network by design.

Starvation Attack

A user/node may try to launch a starvation attack by creating a number of bad nodes that do not provide any resources or services to the network, causing existing peers to search through a larger network database, or request more tunnels than should be necessary. An attempt to find useful nodes can be difficult, as there are no differences between them and failing or loaded nodes. However, I2P, by design, maintains a profile of all peers and attempts to identify and ignore poorly performing nodes, making this attack difficult.

Flooding Attack

In a flooding attack, the malicious user sends a large number of messages to the target’s inbound tunnels or to the network at large.

The targeted user can, however:

- detect this by the contents of the message and because the tunnel’s tests will fail;

- identify the unresponsive tunnels, ignore them and build new ones;

- choose to throttle the number of messages a tunnel can receive.

Although I2P has no defences against a network flooding attack, it is incredibly difficult to flood the network.

Tor Network

What is Tor?

Tor is a free and open-source anonymity/privacy tool, meant to protect a user’s location and identity. The name is derived from the acronym for the original software project name, The Onion Router ([17], [18]). This refers to the way in which Tor protects a user’s data, by wrapping it in multiple layers of encryption, similar to the layers of an onion.

Tor uses a unique system that was originally developed by the US Navy to protect government intelligence communications. Naval Research Laboratory released the Tor code under a free license and the Tor Project was founded in 2006. With the help of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), further research and development of Tor have continued as a Free and Open Source Project. The Tor network service is run by a worldwide community of volunteers and are not controlled by any corporate or government agencies.

The Tor network service is the heart of the Tor project. The Tor Browser and other tools, such as OnionShare, run on top of or via the Tor network. These tools are meant to make using the Tor network as simple and secure as possible.

Some tools, such as the Tor Browser Bundle, come as a single downloadable and installable package containing everything needed to use the Tor network and be anonymous.

Almost any network tool or application that can be configured to use a Socket Secure (SOCKS) proxy can be set up to use the Tor network service.

How does Tor Work?

Before Tor data enters the Tor network, it is bundled into nested layers of encrypted packets of the same size. These packets are then routed through a random series of volunteer-operated servers called relay nodes. Each time the Tor data passes through one of these relays, a layer of encryption is removed to reveal the location of the next relay. When the data reaches the final relay on its path, the last layer of encryption is removed and the data is sent to its final destination.

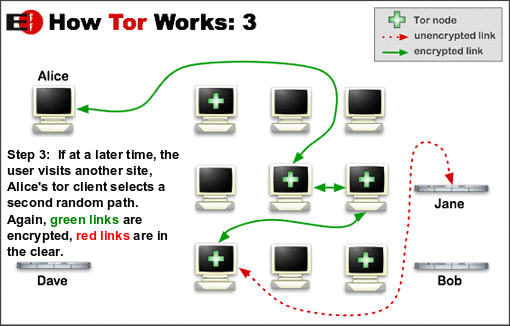

Relay nodes, such as I2P’s nodes, are responsible for creating hops through which data is routed before reaching its intended destination on the Internet. They work by incrementally building a circuit of encrypted connections through relays on the network. The circuit is extended one hop at a time. Each relay along the way knows only which relay gave it data and which relay it is giving data to. No individual relay ever knows the complete path that a data packet has taken. Also, no request uses the same path. Later requests are given a new circuit, to keep people from linking a user’s earlier actions to new actions. This process is also known as Onion Routing [14], and is illustrated in Figure 4:

Figure 4: How Tor Works [13]

How does Onion Routing Work?

Onion Routing is essentially a distributed overlay network designed to anonymize Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) based applications such as web browsing, secure shell and instant messaging. Clients choose a path through the network and build a circuit in which each node in the path knows its predecessor and successor, but no other nodes in the circuit. Traffic flows down the circuit in fixed-size cells, which are unwrapped by a symmetric key at each node (similar to the layers of an onion) and relayed downstream [14]. Each relay can only decrypt enough data to learn the location of the previous and next relay. Since each path is randomly generated and the relays do not keep records, it is nearly impossible for your activity to be traced back to you through Tor’s complex network [21].

An .onion address points to some resource on the Tor network called a hidden service or an onion service. Onion

services are generally only accessible by using the Tor network. As an example, if the DuckDuckGo Search engine onion

address (https://3g2upl4pq6kufc4m.onion/) is visited, the request is routed through the Tor network without the client

knowing the host IP address of the server. The onion address is practically meaningless without it being routed through

and resolved by the Tor network. Traffic between a Tor client and an .onion site should never leave the Tor network,

thus making the network traffic safer and more anonymous than publicly hosted sites. An .onion address is a domain

name that is not easy to remember or find, as there are no directory services. It generally consists of opaque,

non-mnemonic, 16- or 56-character alpha-semi-numerical strings that are generated on a cryptographically hashed public

key. The Top Level Domain (TLD) .onion is not a true domain and cannot be found or queried on the Internet, but only

inside the Tor network ([19]], [23], [24]).

The designated use of relay nodes in the Tor network gives the network the following important characteristics [13]:

- The stability of the network is proportional to the number of relay nodes in the network. The fewer the number of relay nodes, the less stable the network becomes.

- The security of the network is also proportional to the number of relay nodes. A network with more active relay nodes is less vulnerable to attacks.

- Finally, the speed of the network is proportional to the number of relay nodes. The more nodes there are, the faster the network becomes.

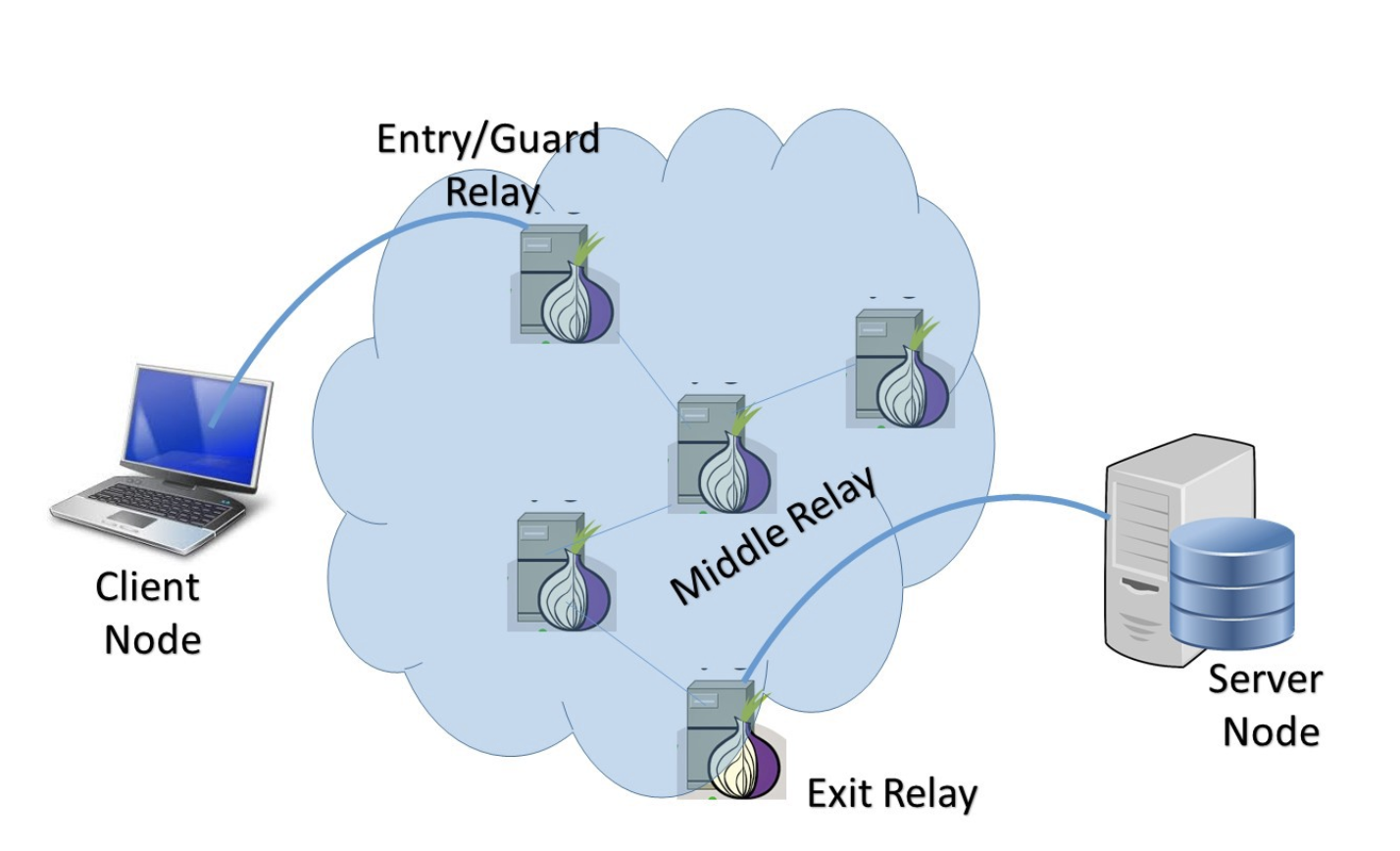

Types of Tor Relays/Nodes Routing

Tor’s relay nodes do not all function in the same way. As shown in Figure 5, there are four types of relay nodes: an entry or guard relay node, a middle relay node, an exit relay node and a bridge relay node.

Figure 5: Tor Circuit [14]

Guard or Entry Relay (Non-exit Relay) Nodes

A guard relay node is the first relay node in the Tor circuit. Each client that wants to connect to the Tor network will first connect to a guard relay node. This means that guard relay nodes can see the IP address of the client attempting to connect. It is worth noting that Tor publishes its guard relay nodes and anyone can see them on websites such as the one in [15]. Since it is possible to see the IP address of a client, there have been cases where attackers have filtered out traffic on the network using circuit fingerprinting techniques such as documented in [16].

Middle Relay Nodes

Middle relay nodes cover most parts of the Tor network and act as hops. They consist of relays through which data is passed in encrypted format. No node knows more than its predecessor and descendant. All the available middle relay nodes show themselves to the guard and exit relay nodes so that any may connect to them for transmission. Middle relay nodes can never be exit relay nodes within the network [13].

Exit Relay Nodes

Exit relay nodes act as a bridge between the Tor network and the Internet. They are Internet public-facing relays, where the last layer of Tor encryption is removed from traffic that can then leave the Tor network as normal traffic that merges into the Internet on its way to its desired destinations on the Internet.

The services to which Tor clients are connecting (website, chat service, email provider, etc.) will see the IP address of the exit relay instead of the real IP addresses of Tor users. Because of this, exit relay node owners are often subjected to numerous complaints, legal notices and shutdown threats [13].

Bridge Relay Nodes

The design of the Tor network means that the IP addresses of Tor relays are public, as previously mentioned, and as shown in [15]. Because of this, Tor can be blocked by governments or ISPs blacklisting the IP addresses of these public Tor nodes. In response to blocking tactics, a special kind of relay called a Bridge should be used, which is a node in the network that is not listed in the public Tor directory. Bridge selection is done when installing the Tor Browser bundle, and makes it less likely to have to deal with complaints or have Internet traffic blocked by ISPs and governments.

Bridge relay nodes are meant for people who want to run Tor from their homes, have a static IP address or do not have much bandwidth to donate [13].

Pitfalls of Using Tor Anonymously - is it Broken?

Although traffic between nodes on the Tor network is encrypted, this does not guarantee anonymity for users. There are a number of pitfalls of using Tor anonymously.

Internet browsers and operating systems, what might seem like a simple request to a URL, could deanonymize somebody.

Older Tor setups needed a user to know how to configure their proxy settings in their operating system and/or browser, in order to use Tor services. This was very easy to get wrong or incomplete, and some users’ information or details could be leaked.

For example, Domain Name System (DNS) requests intended for the Tor network, i.e. .onion address, might be sent

directly to the public DNS server, if the network.proxy.socks_remote_dns was not set to true in FireFox. These DNS

requests could be used to track where a user might be surfing and thus deanonymize the user.

Tor is not broken if Tor services are correctly set up or if the Tor Browser is used correctly. It is very easy to do something that would deanonymize a user, such as use an older browser or tool that is not configured to proxy all traffic via Tor network services.

Another example is if the user logs into a remote service such as Facebook or Gmail, their anonymity at this site is lost. What many people do not know is that other sites use tracking techniques, such as cookies, which could deanonymize the user on other sites too. Further information about online tracking can be found in [25]

However, recent releases of the Tor Browser notify users of updates and also work toward keeping each site isolated in their own Tab or session, addressing old and possibly insecure releases and user tracking via cookies.

Tor some has weaknesses, e.g. if a user is the only person using Tor on their home, office or school network, they could be deanonymized. Another is that a site knows when it has been accessed using Tor. These shortcomings might not be directly an issue with Tor or its encryption, but an expectation of a novice user, using Tor or one of the Tor tools and services.

For an interesting talk about some of the Tor attacks, refer to [26]. The following are two real instances where people using Tor were discovered:

- On 16 December 2013, Harvard University received a bomb threat that was tracked down to Eldo Kim, who was one of the few people using Tor on the campus network when the email had been sent. After questioning, Kim admitted he had sent the hoax bomb threat, as he wanted to get out of an exam [27].

- Hector Xavier Monsegur (Sabu) normally used Tor for connecting to IRC, but was caught not using it once, and the FBI found his home IP. After being caught, he started to collaborate with the FBI. While Monsegur was chatting to Jeremy Hammond on IRC, Hammond let slip details of where he had been arrested before and other groups with which he had been involved. This helped reduce the number of suspects and the FBI was able to get a court order to monitor Internet access and to correlate when Hammond was using Tor [28].

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of Tor:

- It is free and open source.

- It supports Linux, OSX and Windows.

- It is easy to install for supported operating systems.

- It is not controlled by corporate or government agencies.

Disadvantages of Tor:

- It can be slow.

- It does not necessarily encrypt data leaving

Exit Node. This data can be intercepted. - It does not stop somebody from deanonymizing themselves.

- It does not stop interceptors from knowing you are using Tor.

- Its network is not user-friendly, due to its secure and hidden nature.

- Its nodes (relay/bridge) are run by volunteers, who can sometimes be unreliable.

Differences between I2P and Tor

| I2P | Tor |

|---|---|

| Fully peer to peer: self-organizing nodes | Fully peer to peer: volunteer relay nodes |

| Queries NetDB to find destination’s inbound tunnel gateway | Relays data to the closest relay |

| Limited to no exit nodes; internal communication only | Designed and optimized for exit traffic, with a large number of exit nodes |

| Designed primarily for file sharing | Designed for anonymous Internet access |

| Unidirectional tunnels | Rendezvous point |

| Significantly smaller user base | Generally bigger user base |

Conclusion

In summary, Tor and I2P are two network types that anonymize and encrypt data transferred within them. Each network is uniquely designed for a respective function. The I2P network is designed for moving data in a peer-to-peer format, whereas the Tor network is designed for accessing the Internet privately.

Regarding Tor, the following should be kept in mind:

- Anonymity is not confidentiality; Tor by itself does not guarantee anonymity. Total anonymity has many obstacles, not only technology related, but also the human component.

- Tor is not a Virtual Private Network (VPN).

- Tor data leaving the Tor network can be intercepted.

Extensive research exists and continues to find ways to improve the security of these networks in their respective operational designs. This research becomes especially important when control of a network may mean monetary loss, loss of privacy or denial of service.

References

[1] B. Mann, “What Is I2P & How Does It Compare vs. Tor Browser?” [Online.] Available: https://blokt.com/guides/what-is-i2p-vs-tor-browser#How_does_I2P_work. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑18.

“What Is I2P & How Does It Compare vs. Tor Browser?”

[2]: I2P: “I2PTunnel” [online]. Available: https://geti2p.net/en/docs/api/i2ptunnel. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑18.

[3]: C. Egger, J. Schlumberger, C. Kruegel and G. Vigna, “Practical Attacks Against the I2P Network” - Paper [online]. Available: https://sites.cs.ucsb.edu/~chris/research/doc/raid13_i2p.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑18.

“Practical Attacks Against the I2P Network”

[4] N. P. Hoang, P. Kintis, M. Antonakakis and M. Polychronakis, “An Empirical Study of the I2P Anonymity Network and its Censorship Resistance” [online]. Available: https://censorbib.nymity.ch/pdf/Hoang2018a.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑18.

“An Empirical Study of the I2P Anonymity Network and its Censorship Resistance”

[5] K. Alachkar and D. Gaastra, “Mitigating Sybil Attacks on the I2P Network Using Blockchain” - Presentation [online]. Available: https://www.delaat.net/rp/2017-2018/p97/presentation.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

“Mitigating Sybil Attacks on the I2P Network Using Blockchain”

[6] K. Alachkar and D. Gaastra, “Blockchain-based Sybil Attack Mitigation: A Case Study of the I2P Network” - Report [online]. Available: https://delaat.net/rp/2017-2018/p97/report.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

“Blockchain-based Sybil Attack Mitigation: A Case Study of the I2P Network”

[7] I2P: “The Network Database” [online]. Available: https://geti2p.net/en/docs/how/network-database. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

[8] H. Vhora and G. Khilari, “Defending Eclipse Attack in I2P using Structured Overlay Network” [online]. Available: http://ijsetr.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IJSETR-VOL-4-ISSUE-5-1515-1518.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

“Defending Eclipse Attack in I2P using Structured Overlay Network”

[9] M. Ehlert, “I2P Usability vs. Tor Usability - A Bandwidth and Latency Comparison” [online]. Available: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/aa81/79d3da24b643a4d004c44ebe543000295d51.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

“I2P Usability vs. Tor Usability - A Bandwidth and Latency Comparison”

[10] I2P: “I2P Compared to Tor” [online]. Available: https://geti2p.net/en/comparison/tor. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

[11] I2P: “I2P Compared to Tor and Freenet” [online]. Available: http://www.geti2p.org/how_networkcomparisons.html. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑20.

“I2P Compared to Tor and Freenet”

[12] T. de Boer and V. Breider: “Invisible Internet Project - MSc Security and Network Engineering Research Project.” [online]. Available: https://www.delaat.net/rp/2018-2019/p63/report.pdf Date accessed: 2019‑07‑10.

[13] Tor, “Tor Project: How it works” [online]. Available: https://2019.www.torproject.org/about/overview.html.en Date accessed: 2019‑08‑05.

[14] R. Dingledine, N Mathewson and P. Syverson, “Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router” [online] Available: https://svn.torproject.org/svn/projects/design-paper/tor-design.html Date accessed: 2019‑08‑05.

[15] Tor, “Tor Network Status” [online]

Available: https://torstatus.blutmagie.de/ Date accessed: 2019‑08‑05.

[16] A. Kwon, M. AlSabah, D. Lazar, M. Dacier and S. Devadas, “Circuit Fingerprinting Attacks: Passive Deanonymization of Tor Hidden Service” [online] Available: https://people.csail.mit.edu/devadas/pubs/circuit_finger.pdf Date accessed: 2019‑08‑05.

[17] Tor Project: “Download for Tor Browser” [online]. Available: https://www.torproject.org/. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑16.

[18] Wikipedia: “Tor (Anonymity Network)” [online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tor_(anonymity_network). Date accessed: 2019‑05‑16.

[19] DuckDuckGo Search Engine inside Tor [online]. Available: https://3g2upl4pq6kufc4m.onion/. Note: This link will not work unless Tor or the Tor Browser is used. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑16.

“DuckDuckGo Search Engine - link will not work unless Tor or Tor Browser is used”

[20] Tor Project: “Check” [online]. Available: https://check.torproject.org/. Note: This link will help the user identify if Tor or the Tor Browser is been used. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑16

“Tor Project: Check - link will help user identify Tor or Tor Browser is been used”

[21] Tor Project: “Overview” [online]. Available: https://2019.www.torproject.org/about/overview.html.en. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑16.

[22] Tor Project: “The Tor Relay Guide” [online]. Available: https://trac.torproject.org/projects/tor/wiki/TorRelayGuide. Date accessed: 2019‑08‑14.

[23] Wikipedia: “.onion” [online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.onion. Date accessed: 2019‑08‑22.

[24] Tor Project: “How do I access onion services?” [online]. Available: https://2019.www.torproject.org/docs/faq#AccessOnionServices. Date accessed: 2019‑08‑22.

[25] R. Heaton: “How Does Online Tracking Actually Work?” [online]. Available: https://robertheaton.com/2017/11/20/how-does-online-tracking-actually-work/. Date accessed: 2019‑07‑25.

“Robert Heaton: How does online tracking actually work?”

[26] YouTube: “DEF CON 22 - Adrian Crenshaw - Dropping Docs on Darknets: How People Got Caught” [online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQ2OZKitRwc. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑18.

“YouTube: DEF CON 22 - Adrian Crenshaw - Dropping Docs on Darknets: How People Got Caught”

[27] Ars Technica: “Use of Tor helped FBI ID suspect in bomb hoax case” [online]. Available: https://arstechnica.com/security/2013/12/use-of-tor-helped-fbi-finger-bomb-hoax-suspect/. Date accessed: 2019‑07‑11.

“Ars Technica: Use of Tor helped FBI ID suspect in bomb hoax case”

[28] Ars Technica: “Stakeout: How the FBI tracked and busted a Chicago Anon” [online]. Available: https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2012/03/stakeout-how-the-fbi-tracked-and-busted-a-chicago-anon/. Date accessed: 2019‑07‑11.

“Ars Technica: Stakeout: How the FBI tracked and busted a Chicago Anon”

Appendices

Appendix A: Tor Further Investigation

Onion Services - Tor services that don’t leave the Tor network: https://2019.www.torproject.org/docs/onion-services.html.en.

Appendix B: Tor Links of Interest

- What is Tor Browser?

- The Ultimate Guide to Tor Browser (with Important Tips) 2019

- Metrics of the Tor Project

- Sharing files using Tor

- Blog Post about OnionShare2 and its release

- List of Tor Projects

- Isis Lovecruft’s PDF covering Privacy and Anonymity