Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Mimblewimble $ n\text{-of-}n $ Multiparty Bulletproof UTXO

- Mimblewimble $ m\text{-of-}n $ Multiparty Bulletproof UTXO

- Comparison to Bitcoin

- Conclusions, Observations and Recommendations

- References

- Appendices

- Contributors

Introduction

In Mimblewimble, the concept of a Bitcoin-type multi-signature (multisig) applied to an Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO) does not really exist.

In Bitcoin, multisig payments are usually combined with Pay to Script Hash (P2SH) functionality as a means to send funds to a P2SH payment address, and then to manage its expenditure from there. The redeem script itself sets the conditions that must be fulfilled for the UTXOs linked to the P2SH payment address to be spent ([1], [2]).

Unlike Bitcoin, Mimblewimble transactions do not involve payment addresses, as all transactions are confidential. The only requirement for a Mimblewimble UTXO to be spent is the ability to open (or unlock) the Pedersen Commitment that contains the tokens; it does not require an “owner” signature. A typical Mimblewimble UTXO looks like this [9]:

Another fundamental difference is that for any Mimblewimble transaction, all parties, i.e. all senders and all receivers, must interact to conclude the transaction.

Background

Bitcoin $ m\text{-of-}n $ Multisig in a Nutshell

Multiple use cases of $ m\text{-of-}n $ multisig applications exist, e.g. a $ 1\text{-of-}2 $ petty cash account, a $ 2\text{-of-}2 $ two-factor authentication wallet and a $ 2\text{-of-}3 $ board of directors account [3]. A typical $ 2\text{-of-}3 $ Bitcoin P2SH multisig redeem script (where any two of the three predefined public keys must sign the transaction) has the following form:

redeemScript = <OP_2> <A pubkey> <B pubkey> <C pubkey> <OP_3> OP_CHECKMULTISIG

The P2SH payment address is the result of the redeem script double hashed with SHA-256 and RIPEMD-160 and then

Base58Check encoded with a prefix of 0x05:

redeemScriptHash = RIPEMD160(SHA256(redeemScript))

P2SHAddress = base58check.Encode("05", redeemScriptHash)

Multiple payments can now be sent to the P2SH payment address. A generic funding transaction’s output script for the P2SH payment address has the following form, irrespective of the redeem script’s contents:

scriptPubKey = OP_HASH160 <redeemScriptHash> OP_EQUAL

with OP_HASH160 being the combination of SHA-256 and RIPEMD-160. The $ 2\text{-of-}3 $ multisig redeem transaction’s input script

would have the following form:

scriptSig = OP_0 <A sig> <C sig> <redeemScript>

and the combined spending and funding transaction script (validation script) would be

validationScript = OP_0 <A sig> <C sig> <redeemScript> OP_HASH160 <redeemScriptHash> OP_EQUAL

When validationScript is executed, all values are added to the execution stack in sequence. When opcode OP_HASH160

is encountered, the preceding value <redeemScript> is hashed and added to the stack; and when opcode OP_EQUAL is

encountered, the previous two values, hash of the <redeemScript> and <redeemScriptHash>, are compared and removed

from the stack if equal. The top of the stack then contains <redeemScript>, which is evaluated with the two entries on

top of that, <A sig> and <C sig>. The last value in the stack, OP_0, is needed for a glitch in the OP_CHECKMULTISIG

opcode implementation, which makes it pop one more item than those that are available on the stack ([1], [5]).

What is signed?

Partial signatures are created in the same sequence in which the public keys are defined in redeemScript. A simplified

serialized hexadecimal version of the transaction - consisting of the input transaction ID and UTXO index, amount to be

paid, scriptPubKey and transaction locktime - is signed. Each consecutive partial signature includes a serialization

of the previous partial signature with the simplified transaction data to be signed, creating multiple cross-references

in the signed data. This, combined with the public keys, proves the transaction was created by the real owners of the

bitcoins in question ([4], [5], [6]).

How is change redirected to the multisig P2SH?

Bitcoin transactions can have multiple recipients, and one of the recipients of the funds from a P2SH multisig

transaction can be the original P2SHAddress, thus sending change back to itself. Circular payments to the same

addresses are allowed, but they will suffer from a lack of confidentiality. Another way to do this would be to create a

new redeemScript with a new set of public keys every time a P2SH multisig transaction is done to collect the change,

but this would be more complex to manage [4].

Security of the Mimblewimble Blockchain

A Mimblewimble blockchain relies on two complementary aspects to provide security: Pedersen Commitments and range proofs (in the form of Bulletproof range proofs). Pedersen Commitments, e.g. $ C(v,k) = (vH + kG) $, provide perfectly hiding and computationally binding commitments. (Refer to Appendix A for all notation used.)

In Mimblewimble, this means that an adversary, with infinite computing power, can determine alternate pairs $ v ^\prime , k ^\prime $ such that $ C(v,k) = C(v ^\prime , k ^\prime) $ in a reasonable time, to open the commitment to another value when challenged (computationally binding). However, it will be impossible to determine the specific pair $ v, k $ used to create the commitment, because there are multiple pairs that can produce the same $ C $ (perfectly hiding).

In addition to range proofs assuring that all values are positive and not too large, strictly in the range $ [0,2^{64} - 1] $, it also prohibits third parties locking away one’s funds, as demonstrated in the next section. Since Mimblewimble commitments are totally confidential and ownership cannot be proved, anyone can try to spend or mess with unspent coins embedded in those commitments. Fortunately, any new UTXO requires a range proof, and this is impossible to create if the input commitment cannot be opened.

The importance of Range Proofs

The role that Bulletproof range proofs play in securing the blockchain can be demonstrated as follows. Let $ C_a(v_1 , k_1) $ be the “closed” input UTXO commitment from Alice that a bad actor, Bob, is trying to lock away. Bob knows that all commitments in a Mimblewimble blockchain are additionally homomorphic. This means that he can theoretically use Alice’s commitment as input and create a new opposing output in a transaction that sums to a commitment of the value $ 0 $, i.e. $ (\mathbf{0}) $. For this opposing output, Bob will attempt to add an additional blinding factor $ k_{x} $ to the commitment in such a way that the miners validating the transactions will not complain.

A valid Mimblewimble transaction would have the following form:

\[\begin{aligned} C_\mathrm{locked}(v_1 , k_1 + k_x) - C_a(v_1 , k_1) - C_b(v_2 , k_2) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \\\\ \\\\ (v_1 H + (k_1 + k_x) G) - (v_1 H + k_1 G) - (v_2 H + k_2 G) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \end{aligned} \tag{1}\]where the unspent-hiding-blinding commitment from Alice is $ (v_1 H + k_1 G) $ and the value of $ (v_2 H + k_2 G) $ is equal to $ \mathrm{fee} \cdot H $ to be paid to the miner. The newly created commitment $ (v_1 H + (k_1 + k_x) G) $ would be equally unspendable by Alice and Bob, because neither of them would know the total blinding factor $ k_1 + k_x $. Fortunately, in order to construct a Bulletproof range proof for the new output $ (v_1 H + (k_1 + k_x) G) $ as required by transaction validation rules, the values of $ v_1 $ and $ k_1 + k_x $ must be known, otherwise the prover (i.e. Bob) would not be able to convince an honest verifier (i.e. the miner) that $ v_1 $ is non-negative (i.e. in the range $ [0,2^n - 1] $).

If Bob can convince Alice that she must create a fund over which both of them have signing powers ($ 2\text{-of-}2 $ multisig), it would theoretically be possible to create the required Bulletproof range proof for relation (1) if they work together to create it.

Secure Sharing Protocol

Multiple parties working together to create a single transaction that involves multiple steps, need to share information in such a way that what they shared cannot work against them. Each step requires a proof, and it should not be possible to replay an individual step’s proof in a different context. Merlin transcripts [7] is an excellent example of a protocol implementation that achieves this. For the purposes of this report, a simple information sharing protocol is proposed that can be implemented with Merlin transcripts [7].

Mimblewimble $ n\text{-of-}n $ Multiparty Bulletproof UTXO

Simple Sharing Protocol

Alice, Bob and Carol agree to set up a multiparty $ 3\text{-of-}3 $ multisig fund that they can control together. They decide to use a sharing hash function $ val_H = \text{H}_{s}(arg) $ as a handshaking mechanism for all information they need to share. The first step is to calculate the hash $ val_H $ for the value $ arg $ they want to commit to in sharing, and to distribute it to all parties. They then wait until all other parties’ commitments have been received. The second step is to send the actual value they committed to all parties, to then verify each value against its commitment. If everything matches up, they proceed; otherwise they stop and discard everything they have done.

This ensures that public values for each step are not exposed until all commitments have been received. They will apply this simple sharing protocol to all information they need to share with each other. This will be denoted by $ \text{share:} $.

Setting up the Multiparty Funding Transaction

In the transaction Alice, Bob and Carol want to set up, $ C_m $ is the multiparty shared commitment that contains the funds, and $ C_a $, $ C_b $ and $ C_c $ are their respective input contributions. This transaction looks as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} C_m(v_1, \sum _{j=1}^3 k_jG) - C_a(v_a, k_a) - C_b(v_b, k_b) - C_c(v_c, k_c) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \\\\ (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) - (v_aH + k_aG) - (v_bH + k_bG) - (v_cH + k_cG) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \end{aligned} \tag{2}\]In order for this scheme to work, they must be able to jointly sign the transaction with a Schnorr signature, while keeping their portion of the shared blinding factor secret. Each of them creates their own private blinding factor $ k_n $ for the multiparty shared commitment and shares the public blinding factor $ k_nG $ with the group:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace k_1G, k_2G, k_3G \rbrace \tag{3}\]They proceed to calculate their own total excess blinding factors as $ x_{sn} = \sum k_{n(change)} - \sum k_{n(inputs)} - \phi_n $, with $ \phi_n\ $ being a random offset of their own choosing (in this example there is no change):

\[\begin{aligned} x_{sa} &= 0 - k_a - \phi_a \\\\ x_{sb} &= 0 - k_b - \phi_b \\\\ x_{sc} &= 0 - k_c - \phi_c \end{aligned} \tag{4}\]The offset $ \phi_n $ is introduced to prevent someone else linking this transaction’s inputs and outputs when analyzing the Mimblewimble block, and will be used later on to balance the transaction. They consequently share the public value of the excess $ x_{sn}G $ with each other:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace x_{sa}G, x_{sb}G, x_{sc}G \rbrace \tag{5}\]They now have enough information to calculate the aggregated public key for the signature:

\[\begin{aligned} P_{agg} = (k_1G + x_{sa}G) + (k_2G + x_{sb}G) + (k_3G + x_{sc}G) \\\\ P_{agg} = (k_1G - (k_a + \phi_a)G) + (k_2G - (k_b + \phi_b)G) + (k_3G - (k_c + \phi_c)G) \end{aligned} \tag{6}\]Each party also selects a private nonce $ r_n $, shares the public value $ r_nG $ with the group,

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace r_aG, r_bG, r_cG \rbrace \tag{7}\]and calculates the aggregated public nonce for the signature:

\[R_{agg} = r_aG + r_bG + r_cG \tag{8}\]The signature challenge $ e $ can now be calculated:

\[e = \text{Hash}(R_{agg} \| P_{agg} \| m) \mspace{18mu} \text{ with } \mspace{18mu} m = \mathrm{fee} \cdot H \|height \tag{9}\]Each party now uses their private nonce $ r_n $, secret blinding factor $ k_n $ and excess $ x_{sn} $ to calculate a partial Schnorr signature $ s_n $:

\[\begin{aligned} s_a &= r_a + e \cdot (k_1 + x_{sa}) \\\\ s_b &= r_b + e \cdot (k_2 + x_{sb}) \\\\ s_c &= r_c + e \cdot (k_3 + x_{sc}) \end{aligned} \tag{10}\]These partial signatures are then shared with the group to be aggregated:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace s_a, s_b, s_c \rbrace \tag{11}\]The aggregated Schnorr signature for the transaction is then simply calculated as

\[s_{agg} = s_a + s_b + s_c \tag{12}\]The resulting signature for the transaction is the tuple $ (s_{agg},R_{agg}) $. To validate the signature, publicly shared aggregated values $ R_{agg} $ and $ P_{agg} $ will be needed:

\[s_{agg}G \overset{?}{=} R_{agg} + e \cdot P_{agg} \tag{13}\]To validate that no funds are created, the total offset must also be stored in the transaction kernel, so the parties also share their offset and calculate the total:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace \phi_a, \phi_b, \phi_c \rbrace \\\\ \phi_{tot} = \phi_a + \phi_b + \phi_c \end{aligned} \tag{14}\]The transaction balance can then be validated to be equal to a commitment to the value $ 0 $ as follows:

\[(v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) - (v_aH + k_aG) - (v_bH + k_bG) - (v_cH + k_cG) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H \overset{?}{=} (0H + (P_{agg} + \phi_{tot}G)) \tag{15}\]Creating the Multiparty Bulletproof Range Proof

One crucial aspect in validating the transaction is still missing, i.e. each new UTXO must also include a Bulletproof range proof. Up to now, Alice, Bob and Carol could each keep their portion of the shared blinding factor $ k_n $ secret. The new combined commitment they created $ (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) $ cannot be used as is to calculate the Bulletproof range proof, otherwise the three parties would have to give up their portion of the shared blinding factor. Now they need to use a secure method to calculate their combined Bulletproof range proof.

Utilizing Bulletproofs MPC Protocol

This scheme involves coloring the UTXO to enable attachment of additional proof data, a flag to let the miners know that they must employ a different set of validation rules and a hash of the UTXO and all metadata. The Bulletproofs Multiparty Computation (MPC) protocol can be used in a special way to construct a range proof that can be validated by the miners. Aggregating the range proofs using this protocol provides a huge space saving; a single Bulletproof range proof consists of 672 bytes, whereas aggregating 16 only consists of 928 bytes [11]. For this scheme, the simple information sharing protocol will not be adequate; an efficient, robust and secure implementation of the Bulletproof MPC range proof such as that done by Dalek Cryptography [10] is suggested.

This scheme works as follows. Alice, Bob and Carol proceed to calculate an aggregated MPC Bulletproof range proof for the combined multiparty funds, but with each using their own secret blinding factor in the commitment. They therefore construct fake commitments that will be used to calculate fake range proofs as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Alice's fake commitment:} \mspace{18mu} C_1(\frac{v_1}3,k_1) &= (\frac{v_1}3H + k_1G) \\\\ \text{Bob's fake commitment:} \mspace{18mu} C_2(\frac{v_1}3,k_2) &= (\frac{v_1}3H + k_2G) \\\\ \text{Carol's fake commitment:} \mspace{18mu} C_3(\frac{v_1}3,k_3) &= (\frac{v_1}3H + k_3G) \end{aligned} \tag{16}\]Notice that

\[\begin{aligned} C_m(v_1, k_1 + k_2 + k_3) &= C_1(\frac{v_1}3,k_1) + C_2(\frac{v_1}3,k_2) + C_3(\frac{v_1}3,k_3) \\\\ (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) &= (\frac{v_1}3H + k_1G) + (\frac{v_1}3H + k_1G) + (\frac{v_1}3H + k_1G) \end{aligned} \tag{17}\]and that rounding implementation of $ ^{v_1} / _3 $ can ensure that adding these components for all parties will produce the original value $ v_1 $.

Running the Bulletproof MPC range proof will result in a proof share for each party for their fake commitments, which will be aggregated by the dealer according to the MPC protocol. Any one of the party members can be the dealer, as the objective here is just to create the aggregated range proof. Let the aggregated range proof for the set $ \lbrace C_1, C_2, C_3 \rbrace $ be depicted by $ RP_{agg} $. The UTXO will then consist of the tuple $ (C_m , RP_{agg}) $ and metadata $ \lbrace flag, C_1, C_2, C_3, hash_{C_{m}} \rbrace $. The hash that will secure the metadata is proposed as:

\[hash_{C_m} = \text{Hash}(C_m \| RP_{agg} \| flag \| C_1 \| C_2 \| C_3) \tag{18}\]Range proof validation by miners will involve

\[\begin{aligned} hash_{C_m} &\overset{?}{=} \text{Hash}(C_m \| RP_{agg} \| flag \| C_1 \| C_2 \| C_3) \\\\ C_m &\overset{?}{=} C_1 + C_2 + C_3 \\\\ \text{verify: } &RP_{agg} \text{ for set } \lbrace C_1, C_2, C_3 \rbrace \end{aligned} \tag{19}\]instead of

\[\text{verify: } RP_m \text{ for } C_m \tag{20}\]Utilizing Grin’s Shared Bulletproof Computation

Grin extended the Inner-product Range Proof implementation to allow for multiple parties to jointly construct a single Bulletproof range proof $ RP_m $ for a known value $ v $, where each party can keep their partial blinding factor secret. The parties must share committed values deep within the inner-product range proof protocol ([12], [13], [14]).

In order to construct the shared Bulletproof range proof $ RP_m $, each party starts to calculate their own range proof for commitment $ C_m(v_1, \sum _{j=1}^3 k_jG) $ as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Alice:} \mspace{18mu} C_1(v_1,k_1) &= (v_1H + k_1G) \\\\ \text{Bob:} \mspace{18mu} C_2(0,k_2) &= (0H + k_2G) \\\\ \text{Carol:} \mspace{18mu} C_3(0,k_3) &= (0H + k_3G) \end{aligned} \tag{21}\]With this implementation, Alice needs to act as the dealer. When they get to steps (53) to (61) in Figure 5 of the inner-product range proof protocol, they introduce the following changes:

- Each party shares $ T_{1_j} $ and $ T_{2_j} $ with all other parties.

- Each party calculates $ T_1 = \sum_{j=1}^k T_{1_j} $ and $ T_2 = \sum_{j=1}^k T_{2_j} $.

- Each party calculates $ \tau_{x_j} $ based on $ T_1 $ and $ T_2 $.

- Each party shares $ \tau_{x_j} $ with the dealer.

- The dealer calculates $\tau_x = \sum_{j=1}^k \tau_{x_j} $.

- The dealer completes the protocol, using their own private $ k_1 $, where a further blinding factor is required, and calculates $ RP_m $.

Using this approach, the resulting shared commitment for Alice, Bob and Carol is

\[C_m(v_1, \sum _{j=1}^3 k_jG) = (v_1H + \sum _{j=1}^3 k_jG) = (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) \tag{22}\]with the UTXO tuple being $ (C_m , RP_m) $. Range proof validation by miners will involve verifying $ RP_m $ for $ C_m $.

Comparison of the Two Bulletproof Methods

| Consideration | Using Dalek’s Bulletproofs MPC Protocol | Using Grin’s Multiparty Bulletproof |

|---|---|---|

| Rounds of communication | Three | Two |

| Information sharing security | Use of Merlin transcripts, combined with the MPC protocol, makes this method more secure against replay attacks. | No specific sharing protocol suggested, but potentially easy to implement, as described here. |

| Guarantee of honest dealer | With the standard MPC protocol implementation, there is no guarantee that the dealer behaves honestly according to the protocol and generates challenges honestly, but this aspect could be improved as suggested in that report. | Although each party independently computes challenges themselves, it isn’t clear what the implications of a dishonest dealer would be in practice. |

| Size of the Bulletproof | Logarithmic Bulletproof range proof size, i.e. 672 bytes up to 928 bytes for 16 range proofs. | Single Bulletproof range proof size of 672 bytes. |

| Colored coin | Coins are colored, i.e. distinguishable from normal commitments in the blockchain due to additional metadata. | Coins do not need to be colored, i.e. it may look exactly like any other commitment. |

| Wallet reconstructability | Each individual range proof’s data is accessible within the aggregated range proof. It is possible to identify the colored coin and then to reconstruct the wallet if the initial blinding factor seed is remembered in conjunction with Bulletproof range proof rewinding. | The wallet cannot be reconstructed, as a single party’s blinding factor cannot be distinguished from the combined range proof. Even if these coins were colored with a flag to make them identifiable, it would not help. |

| Hiding and binding commitment | The main commitment and additional commitments in the UTXO’s metadata retain all hiding and binding security aspects of the Pederson Commitment. | The commitment retains all hiding and binding security aspects of the Pederson Commitment. |

Spending the Multiparty UTXO

Alice, Bob and Carol had a private bet going that Carol won, and they agree to spend the multiparty UTXO to pay Carol her winnings, with the change being used to set up a consecutive multiparty UTXO. This transaction looks as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} C^{'}_c(v^{'}_c, k^{'}_c) + C^{'}_m(v^{'}_1, \sum _{j=1}^3 k^{'}_{j}G) - C_m(v_1, \sum _{j=1}^3 k_jG) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \\\\ (v^{'}_cH + k^{'}_cG) + (v^{'}_1H + (k^{'}_1 + k^{'}_2 + k^{'}_3)G) - (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H &= (\mathbf{0}) \end{aligned} \tag{23}\]Similar to the initial transaction, they each create their own private blinding factor $ k^{‘}_n $ for the new multiparty UTXO and share the public blinding factor $ k^{‘}_nG $ with the group. Carol also shares the public blinding factor $ k^{‘}_cG $ for her winnings:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{share:} \mspace{9mu} &\lbrace k^{'}_1G, k^{'}_2G, k^{'}_3G \rbrace \\\\ \text{share:} \mspace{9mu} &\lbrace k^{'}_cG \rbrace \end{aligned} \tag{24}\]As before, they calculate their own total excess blinding factors as $ x^{‘}_{sn} = \sum k^{‘}_{n(change)} - \sum k^{‘}_{n(inputs)} - \phi^{‘}_n $:

\[\begin{aligned} x^{'}_{sa} &= 0 - k_1 - \phi^{'}_a \\\\ x^{'}_{sb} &= 0 - k_2 - \phi^{'}_b \\\\ x^{'}_{sc} &= 0 - k_3 - \phi^{'}_c \end{aligned} \tag{25}\]They share the public value of the excess $ x^{‘}_{sn}G $ with each other:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace x^{'}_{sa}G, x^{'}_{sb}G, x^{'}_{sc}G \rbrace \tag{26}\]The aggregated public key for the signature can then be calculated as:

\[\begin{aligned} P^{'}_{agg} = (k^{'}_1G + x^{'}_{sa}G) + (k^{'}_2G + x^{'}_{sb}G) + (k^{'}_3G + x^{'}_{sc}G + k^{'}_cG) \\\\ P^{'}_{agg} = (k^{'}_1G - (k_1 + \phi^{'}_a)G) + (k^{'}_2G - (k_2 + \phi^{'}_a)G) + (k^{'}_3G - (k_3 + \phi^{'}_a)G + k^{'}_cG) \end{aligned} \tag{27}\]Each party again selects a private nonce $ r^{‘}_n $, shares the public value $ r^{‘}_nG $ with the group,

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace r^{'}_aG, r^{'}_bG, r^{'}_cG \rbrace \tag{28}\]and calculates the aggregated public nonce for the signature:

\[R^{'}_{agg} = r^{'}_aG + r^{'}_bG + r^{'}_cG \tag{29}\]The new signature challenge $ e^{‘} $ is then calculated as:

\[e^{'} = \text{Hash}(R^{'}_{agg} \| P^{'}_{agg} \| m) \mspace{18mu} \text{ with } \mspace{18mu} m = \mathrm{fee} \cdot H \|height \tag{30}\]Each party now calculates their partial Schnorr signature $ s^{‘}_n $ as before, except that Carol also adds her winnings’ blinding factor $ k^{‘}_c $ to her signature:

\[\begin{aligned} s^{'}_a &= r^{'}_a + e^{'} \cdot (k^{'}_1 + x^{'}_{sa})\\\\ s^{'}_b &= r^{'}_b + e^{'} \cdot (k^{'}_2 + x^{'}_{sa})\\\\ s^{'}_c &= r^{'}_c + e^{'} \cdot (k^{'}_3 + x^{'}_{sa} + k^{'}_c) \end{aligned} \tag{31}\]These partial signatures are then shared with the group

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace s^{'}_a, s^{'}_b, s^{'}_c \rbrace \tag{32}\]to enable calculation of the aggregated Schnorr signature as

\[s^{'}_{agg} = s^{'}_a + s^{'}_b + s^{'}_c \tag{33}\]The resulting signature for the transaction is the tuple $ (s^{‘}_{agg},R^{‘}_{agg}) $. The signature is again validated as done previously, using the publicly shared aggregated values $ R^{‘}_{agg} $ and $ P^{‘}_{agg} $:

\[s^{'}_{agg}G \overset{?}{=} R^{'}_{agg} + e^{'} \cdot P^{'}_{agg} \tag{34}\]Again the parties also share their own personal offset so that the total offset can be calculated:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace \phi^{'}_a, \phi^{'}_b, \phi^{'}_c \rbrace \\\\ \phi^{'}_{tot} = \phi^{'}_a + \phi^{'}_b + \phi^{'}_c \tag{35}\]Lastly, the transaction balance can be validated to be equal to a commitment to the value $ 0 $:

\[(v^{'}_cH + k^{'}_cG) + (v^{'}_1H + (k^{'}_1 + k^{'}_2 + k^{'}_3)G) - (v_1H + (k_1 + k_2 + k_3)G) + \mathrm{fee} \cdot H \overset{?}{=} (0H + (P^{'}_{agg} + \phi^{'}_{tot}G)) \tag{36}\]Mimblewimble $ m\text{-of-}n $ Multiparty Bulletproof UTXO

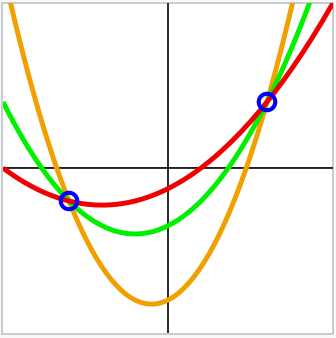

As mentioned in the Introduction, Mimblewimble transactions cannot utilize a smart/redeem script in the form of a P2SH, but similar functionality can be implemented in the users’ wallets. For the $ m\text{-of-}n $ multiparty Bulletproof UTXO, Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme (SSSS) ([8], [15]) will be used to enable $ m\text{-of-}n $ parties to complete a transaction. The SSSS is a method for $ n $ parties to carry one shard (share) $ f(i) $ for $ i \in \lbrace 1 , \ldots , n \rbrace $ each of a secret $ s $, such that any $ m $ of them can reconstruct the message. The basic idea behind the SSSS is that it is possible to draw an infinite number of polynomials of degree $ m $ through $ m $ points, whereas $ m+1 $ points are required to define a unique polynomial of degree $ m $. A simplified illustration is shown in Figure 1; the SSSS uses polynomials over a finite field, which is not representable on a two-dimensional plane [19].

The shards will be distributed according to Pedersen’s Verifiable Secret Sharing (VSS) scheme, which extends the SSSS, where the dealer commits to the secret $ s $ itself and the coefficients of the sharing polynomial $ f(x) $. This is broadcast to all parties, with each receiving a blinding factor shard $ g(i) $ corresponding to their secret shard $ f(i) $. This will enable each party to verify that their shard is correct.

Secret Sharing

Our friends Alice, Bob and Carol decide to set up a $ 2\text{-of-}3 $ scheme, whereby any two of them can authorize a spend of their multiparty UTXO. They also want to be able to set up the scheme such that they can perform three rounds of spending, with the last round being the closing round. Something they were all thinking about was how to share pieces of their blinding factor with each other in a secure and reconstructable fashion. They have heard of Pedersen’s VSS scheme and decide to use that.

Multiple Rounds’ Data

The parties will each pre-calculate $ three $ private blinding factors $ k_{n\text{-}i} $ and shard it according to Pedersen’s VSS scheme. The scheme requires $ three $ shard tuples $ (k_{n\text{-}party\text{-}i}, b_{n\text{-}party\text{-}i}) $ and $ three $ vectors of commitments $\mathbf{C}_{2}( k_{party\text{-}1})$ for each round. (Appendix C shows an example of Alice’s sharing shards for one private blinding factor.) Whenever a set of information for each blinding factor is shared, the parties immediately verify the correctness of the shards they received by following the verification step in Pedersen’s VVS protocol. They continue to do this until they have all their information set up, ready and stored in their wallets.

| Round | Blinding Factor |

Vectors of Commitments |

Alice’s Shards |

Bob’s Shards |

Carol’s Shards |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice: $ (k_{1\text{-}1}, b_{1\text{-}1}) $ Bob: $ (k_{2\text{-}1}, b_{2\text{-}1}) $ Carol: $ (k_{3\text{-}1}, b_{3\text{-}1})$ |

$\mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{1\text{-}1})$ $ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{2\text{-}1}) $ $\mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{3\text{-}1}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}a1}, b_{1\text{-}a1}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}a1}, b_{2\text{-}a1}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}a1}, b_{3\text{-}a1}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}b1}, b_{1\text{-}b1}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}b1}, b_{2\text{-}b1}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}b1}, b_{3\text{-}b1}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}c1}, b_{1\text{-}c1}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}c1}, b_{2\text{-}c1}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}c1}, b_{3\text{-}c1}) $ |

| 2 | Alice: $ (k_{1\text{-}2}, b_{1\text{-}2}) $ Bob: $ (k_{2\text{-}2}, b_{2\text{-}2}) $ Carol: $ (k_{3\text{-}2}, b_{3\text{-}2}) $ |

$ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{1\text{-}2}) $ $ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{2\text{-}2}) $ $ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{3\text{-}2}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}a2}, b_{1\text{-}a2}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}a2}, b_{2\text{-}a2}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}a2}, b_{3\text{-}a2}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}b2}, b_{1\text{-}b2}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}}b2, b_{2\text{-}b2}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}},b2 b_{3\text{-}b2}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}c2}, b_{1\text{-}c2}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}}c2, b_{2\text{-}c2}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}},c2 b_{3\text{-}c2}) $ |

| 3 | Alice: $ (k_{1\text{-}3}, b_{1\text{-}3}) $ Bob: $ (k_{2\text{-}3}, b_{2\text{-}3}) $ Carol: $ (k_{3\text{-}3}, b_{3\text{-}3}) $ |

$ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{1\text{-}3}) $ $ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{2\text{-}3}) $ $ \mathbf{C_{2}}( k_{3\text{-}3}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}a3}, b_{1\text{-}a3}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}a3}, b_{2\text{-}a3}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}a3}, b_{3\text{-}a3}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}b3}, b_{1\text{-}b3}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}}b3, b_{2\text{-}b3}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}},b3 b_{3\text{-}b3}) $ |

$ (k_{1\text{-}c3}, b_{1\text{-}c3}) $ $ (k_{2\text{-}}c3, b_{2\text{-}c3}) $ $ (k_{3\text{-}},c3 b_{3\text{-}c3}) $ |

How it Works

The three parties set up the initial multiparty funding transaction and Bulletproof range proof exactly the same as they did for the $ 3\text{-of-}3 $ case. For this, they use the private blinding factors they pre-calculated for round 1. Now, when they decide to spend the multiparty UTXO, only two of them need to be present.

Bob and Carol decide to spend funds, exactly like before, and for this they need to reconstruct Alice’s private blinding factor for round 1 and round 2. Because Alice did not win anything, she does not need to be present to set up a private blinding factor for an output UTXO the way Carol needs to do. Bob and Carol consequently share the shards Alice gave them:

\[\text{share:} \mspace{9mu} \lbrace (k_{1\text{-}b1}, b_{1\text{-}b1}), (k_{1\text{-}c1}, b_{1\text{-}c1}), (k_{1\text{-}b2}, b_{1\text{-}b2}) , (k_{1\text{-}c2}, b_{1\text{-}c2}) \rbrace \tag{37}\]They are now able to reconstruct the blinding factors and verify the commitments to it. If the verification fails, they stop the protocol and schedule a meeting with Alice to have a word with her. With all three together, they will be able to identify the source of the misinformation.

\[\begin{aligned} \text{reconstruct:} \mspace{9mu} (k_{1\text{-}1}, b_{1\text{-}1}), (k_{1\text{-}2}, b_{1\text{-}2}) \\\\ \text{verify:} \mspace{9mu} C(k_{1\text{-}1}, b_{1\text{-}1})_{shared} \overset{?}{=} (k_{1\text{-}1}H + b_{1\text{-}1}G) \\\\ \text{verify:} \mspace{9mu} C(k_{1\text{-}2}, b_{1\text{-}2})_{shared} \overset{?}{=} (k_{1\text{-}2}H + b_{1\text{-}2}G) \end{aligned} \tag{38}\]For this round they choose Bob to play Alice’s part when they set up and conclude the transaction. Bob is able to do this, because he now has Alice’s private blinding factors $ k_{1\text{-}1} $ and $ k_{1\text{-}2} $. When constructing the signature on Alice’s behalf, he chooses a private nonce $ r^{‘}_n $ she does not know, as it will only be used to construct the signature and then never again. Bob and Carol conclude the transaction, let Alice know this and inform her that a consecutive multi-spend needs to start at round 2.

The next time two of our friends want to spend some or all of the remainder of their multiparty UTXO, they will just repeat these steps, starting at round 2. The only thing that will be different will be the person nominated to play the part of the party that is absent; they have to take turns at this.

Spending Protocol

Alice, Bob and Carol are now seasoned at setting up their $ 2\text{-of-}3 $ scheme and spending the UTXO until all funds are depleted. They have come to an agreement on a simple spending protocol, something to help keep all of them honest:

-

All parties must always know who shared shards and who played the missing party’s role for each round. Therefore, all parties must always be included in all sharing communication, even if they are offline. They can then receive those messages when they become available again.

-

The spend is aborted if any verification step does not complete successfully. To recommence, the parties have to cancel all unused shards, calculate new shards for the remainder and start again. For this, all parties need to be present.

-

No party may play the role of an absent party twice in a row. If Alice is absent, which usually happens, Bob and Carol must take turns.

Conclusions, Observations and Recommendations

Comparison to Bitcoin

Given the basic differences between Bitcoin and Mimblewimble as mentioned in the Introduction, and the multiparty payment scheme introduced here, the following observations can be made:

-

Miner Validation

In Bitcoin, the P2SH multisig redeem script is validated by miners whenever a multisig payment is invoked. In addition, they also validate the public keys used in the transaction.

With Mimblewimble multiparty transactions, miners cannot validate who may be part of a multiparty transaction, only that the transaction itself complies with basic Mimblewimble rules and that all Bulletproof range proofs are valid. The onus is on the parties themselves to enforce basic spending protocol validation rules.

-

$ m\text{-of-}n $

In both Bitcoin and Mimblewimble, $ m\text{-of-}n $ transactions are possible. The difference is in where and how validation rules are applied.

-

Security

Bitcoin multiparty transactions are more secure due to the validation rules being enforced by the miners.

-

Complexity

Implementing $ m\text{-of-}n $ multiparty transactions in Mimblewimble will involve wallets to store more data and implement more functionality than when compared to Bitcoin, e.g. Pedersen’s VSS scheme.

General

-

Bulletproof Range Proof

The choice between using Dalek’s Bulletproofs MPC Protocol or Grin’s multiparty Bulletproof to construct a multiparty range proof is important. Although using Dalek’s method involves more rounds of communication, with a slightly larger proof size and the requirement to have the coins colored, it has definite advantages. It trumps on wallet reconstructability and information sharing security while executing the protocol, although the latter could easily be enhanced for the Grin implementation.

-

Practicality

The Mimblewimble multiparty Bulletproof UTXO as proposed can be practically implemented for both the $ n\text{-of-}n $ and $ m\text{-of-}n $ cases.

-

Information Sharing Protocol

The Simple Sharing Protocol as suggested here may need some more work to make it optimal.

-

Generalization

Although all examples presented here were for three parties, this could easily be generalized.

References

[1] “The Best Step-by-Step Bitcoin Script Guide Part 2” [online]. Available: https://blockgeeks.com/guides/bitcoin-script-guide-part-2. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑02.

[2] “Script” [online]. Available: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Script. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

[3] “Multisignature” [online]. Available: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Multisignature. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

[4] “Transaction” [online]. Available: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Transaction. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

[5] S. Pour, “Bitcoin Multisig the Hard Way: Understanding Raw P2SH Multisig Transactions” [online]. Available: https://www.soroushjp.com/2014/12/20/bitcoin-multisig-the-hard-way-understanding-raw-multisignature-bitcoin-transactions. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

“Bitcoin Multisig the Hard Way: Understanding Raw P2SH Multisig Transactions”

[6] GitHub: “gavinandresen/TwoOfThree.sh” [online]. Available: https://gist.github.com/gavinandresen/3966071. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

[7] H.de Valence, I. Lovecruft and O. Andreev, “Merlin Transcripts” [online]. Available: https://merlin.cool/index.html and https://doc-internal.dalek.rs/merlin/index.html. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

[8] T. Pedersen, “Non-interactive and Information-theoretic Secure Verifiable Secret Sharing” [online]. Available: https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs754/2001fa/129.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

“Non-interactive and Information-theoretic Secure Verifiable Secret Sharing”

[9] “GrinExplorer, Block 164,690” [online]. Available: https://grinexplorer.net/block/0000016c1ceb1cf588a45d0c167dbfb15d153c4d1d33a0fbfe0c55dbf7635410. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

[10] “Dalek Cryptography - Crate Bulletproofs - Module bulletproofs::range_proof_mpc” [online]. Available: https://doc-internal.dalek.rs/bulletproofs/range_proof_mpc/index.html. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

“Dalek Cryptography - Crate Bulletproofs Module bulletproofs::range_proof_mpc”

[11] B. Bünz, J. Bootle, D. Boneh, A. Poelstra, P. Wuille and G. Maxwell, “Bulletproofs: Short Proofs for Confidential Transactions and More” (Slides) [online]. Available: https://cyber.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/bpase18.pptx. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑11.

[12] “Grin Multiparty Bulletproof - jaspervdm” [online]. Available: https://i.imgur.com/s7exNSf.png. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

[13] GitHub: “Multi-party bulletproof PR#24” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/secp256k1-zkp/pull/24. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

[14] GitHub: “secp256k1-zkp/src/modules/bulletproofs/tests_impl.h, test_multi_party_bulletproof” [online]. Available: https://github.com/mimblewimble/secp256k1-zkp/blob/master/src/modules/bulletproofs/tests_impl.h. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑10.

“GitHub: secp256k1-zkp/src/modules/bulletproofs/tests_impl.h, test_multi_party_bulletproof”

[15] “MATH3024 Elementary Cryptography and Protocols: Lecture 11, Secret Sharing”, University of Sydney, School of Mathematics and Statistics [online]. Available: http://iml.univ-mrs.fr/~kohel/tch/MATH3024/Lectures/lectures_11.pdf. Date accessed: 2018‑09‑18.

“MATH3024 Elementary Cryptography and Protocols: Lecture 11, Secret Sharing”

[16] I. Coleman, “Online Tool: Shamir Secret Sharing Scheme” [online]. Available: https://iancoleman.io/shamir. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑27.

[17] P. Laud, “Cryptographic Protocols (MTAT.07.005): Secret Sharing”, Cybernetica [online]. Available: https://research.cyber.ee/~peeter/teaching/krprot07s/ss.pdf. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑29.

[18] T. Pedersen, “Distributed Provers and Verifiable Secret Sharing Based on the Discrete Logarithm Problem”, DPB, vol. 21, no. 388, Mar. 1992 [online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.7146/dpb.v21i388.6621. Date accessed: 2019‑06‑03.

“Distributed Provers and Verifiable Secret Sharing Based on the Discrete Logarithm Problem”

[19] Wikipedia: “Shamir’s Secret Sharing” [online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamir%27s_Secret_Sharing. Date accessed: 2019‑05‑06.

Appendices

Appendix A: Notation Used

This section gives the general notation of mathematical expressions used. It provides important pre-knowledge for the remainder of the report.

-

All Pedersen Commitments will be of the elliptic derivative depicted by $ C(v,k) = (vH + kG) $ with $ v $ being the value committed to and $ k $ being the blinding factor.

-

Scalar multiplication will be depicted by “$ \cdot $”, e.g. $ e \cdot (vH + kG) = e \cdot vH + e \cdot kG $.

-

A Pedersen Commitment to the value of $ 0 $ will be depicted by $ C(0,k) = (0H + kG) = (kG) = (\mathbf{0}) $.

-

Let $ \text{H}_{s}(arg) $ be a collision-resistant hash function used in an information sharing protocol where $ arg $ is the value being committed to.

-

Let $ RP_n $ be Bulletproof range proof data for commitment $ C_n $.

-

Let $ RP_{agg} $ be aggregated Bulletproof range proof data for a set of commitments $ \lbrace C_1, C_2, … , C_n \rbrace $.

-

Let $ \mathbf {C_{m}}(v) $ be a vector of commitments $ (C_0 , \ldots , C_{m-1}) $ for value $ v $.

Appendix B: Definition of Terms

Definitions of terms presented here are high level and general in nature. Full mathematical definitions are available in the cited references.

-

Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme: A $ (m, n) $ threshold secret sharing scheme is a method for $ n $ parties to carry shards/shares of a secret message $ s $ such that any $ m $ of them can reconstruct the message. The threshold scheme is perfect if knowledge of $ m − 1 $ or fewer shards provides no information regarding $ s $. Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme provides a perfect $ (m, n) $ threshold scheme using Lagrange interpolation ([15], [17, [19]).

- Given $ m $ distinct points $ (x_i, y_i) $ of the form $ (x_i, f(x_i)) $, where $ f(x) $ is a polynomial of degree less than $ m $, then according to the Lagrange interpolation formula $ f(x) $ and $ f(0) $ is determined by

- Shamir’s scheme is defined for a secret message $ s \in \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} $ with prime $ p $, by setting $ a_0 = f(0) = s$ for a polynomial $ f(x) $, and choosing the other coefficients $ a_1, \ldots , a_{m−1} $ at random in $ \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} $. The trusted party computes $ f(i) $ for all $ 1 \leq i \leq n $, where

- The shards $ (i, f(i)) $ are distributed to the $ n $ distinct parties. Since the secret is the constant term $ s = a_0 = f(0) $, it is recovered from any $ m $ shards $ (i, f(i)) $ for $ I \subset \lbrace 1, \ldots, n \rbrace $ by

“Appendix B: Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme is an (m, n) threshold scheme for n parties to carry shares of a secret message such that any m of them can reconstruct the message.”

-

Pedersen Verifiable Secret Sharing: The Pedersen Verifiable Secret Sharing scheme is a non-interactive $ (m, n) $ threshold VSS scheme that combines Pedersen Commitments and Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme ([8], [17], [18). This is to ensure the dealer gives consistent shares to all parties and that any party can know that the recovered secret is correct.

-

The dealer creates a commitment to the secret $ s $ for a randomly chosen blinding factor $ r $ as $ C_0(s,r) = (sH + rG) $.

-

The dealer constructs the SSSS sharing polynomial $ f(x) $ as before by setting $ a_0 = s $, and randomly choosing $ a_1, \ldots , a_{m−1} $.

-

The dealer also constructs a blinding factor polynomial $ g(x) $, similar to the SSSS polynomial, by setting $ b_0 = r $, and randomly choosing $ b_1, \ldots , b_{m−1} $.

-

The dealer constructs commitments to the secret coefficients of $ f(x) $ as $ C_i(a_i,b_i) = (a_iH + b_iG) $ for $ i \in \lbrace 1, \ldots, m-1 \rbrace $.

-

The dealer broadcasts the vector of commitments $ \mathbf {C_{m}} = (C_0 , \ldots , C_{m-1}) $ to all parties.

-

The dealer calculates $ (f(i), g(i)) $ from polynomials $ f(x), g(x) $ for $ i \in \lbrace 1, \ldots, n \rbrace $ and distributes the individual shards $ (i, f(i), g(i)) $ to the $ n $ distinct parties.

-

Upon receipt of their shard $ (i, f(i), g(i)) $, each party calculates their own commitment $ (f(i)H + g(i)G) $ and verifies that:

-

The secret $ s $ is recovered as before as per the SSSS from any $ m $ shards.

-

In addition to reconstructing the secret $ s $, the following can be done:

- Since the blinding factor is the constant term $ r = b_0 = g(0) $, the blinding factor is recovered from any $ m $ shards $ (i, g(i)) $ for $ I \subset \lbrace 1, \ldots, n \rbrace $ by

- Since $ C_0 $ is the first entry in the vector of commitments $ \mathbf {C_{m}} $, the parties can verify the correctness of the original secret $ s $ that was committed to in the first place when the shards have been shared among the parties as:

-

“Appendix B: The Pedersen Verifiable Secret Sharing scheme is a non-interactive (m, n) threshold scheme that combines Pedersen commitments and Shamir’s Secret Sharing Scheme.”

Appendix C: Shamir’s Secret Sharing Example

One of the private blinding factors Alice calculated and wants to share with Bob and Carol is

Alice’s shard:

Bob’s shard:

Carol’s shard:

Using any two of these shards with the tool provided in [16], Alice’s original private blinding factor can be recreated. Try it out!

Note: This example shows blinding factor shards created with the SSSS tool developed by Coleman [16]. It was merely developed for demonstration purposes and does not make any claims to meet cryptographic security rules other than using secure randomness.