How it all started

If you’re looking for the dry, cut-to-the-bone technical specification for TariScript, then we’ve got your back.

Tari is based on an implementation of the Mimblewimble protocol. Mimblewimble is much more scalable and private than, say, Bitcoin.

One doesn’t get this scalability and privacy for free, I’m afraid. One of the consequences of Mimblewimble is that transactions are interactive. Both parties in a transaction need to be involved in the construction of a valid Mimblewimble transaction.

This is a bit of a bummer if your counterparty is on holiday in Ibiza and you want to send him a payment before your tax returns are due. It also means that “standard” things like tip jars are não fácil in standard Mimblewimble.

Some of the other things we want to be able to do in Tari that are hard (though not impossible in some cases, thanks to scriptless scripts include:

- m-of-n multisig

- Payment channels

- Atomic swaps

- Cross-chain atomic swaps

- Side chain peg-in and peg-out transactions

- Digital asset “cold storage”

… and many other things we haven’t thought of yet.

Fortunately, we think that TariScript is the tool that lets us have cake and eat it. It brings the power and the flexibility of Bitcoin script to Mimblewimble while having a minor effect on privacy and scalability.

TariScript - the basic idea

A quick recap of Mimblewimble transactions

In standard Mimblewimble, to spend a UTXO, one needs knowledge of

- The spend key of the UTXO commitment,

- The value of the UTXO commitment.

You use this knowledge to construct a valid transaction, which contains

- Range proofs for new UTXOs, proving the values are non-negative AND knowledge of the spend key and value,

- A signature on the kernel, proving knowledge of the transaction excess.

Mimblewimble transactions are interactive because the transaction contains information (the spend keys) that must remain secret to each party.

So how can we implement something like one-sided payments in Mimblewimble?

This is where TariScript comes in.

How TariScript works - the 50,000ft view

What if we changed things slightly and added some extra UTXO-spending rules?

Let’s say that, in addition to knowing the spend key and commitment value, we also require you to prove possession of another private key, which we’ll call the script key.

The twist is that we don’t know the script public key until the UTXO script has finished executing 1. By definition, the script public key is whatever remains on the stack after the script has successfully completed execution. Any errors in the script execution, or if there is not exactly one valid public key on the stack after the script has finished running will result in the transaction being rejected.

Think of this as having a door with two locks. Standard Mimblewimble just has one lock. TariScript introduces a second lock, and you need to unlock both to open the door and spend the UTXO.

This lets us do some pretty cool things.

If we lock the first but leave the second lock open, we have our standard Mimblewimble transaction. In TariScript, you can leave the lock open by attaching an empty script to a UTXO.

If we leave the first lock open, or if multiple people have keys to the first lock, then we can provide a script that keeps the second locked until a specific key comes along to open it up. This is Tari in Bitcoin “emulation mode”.

And of course, we could also lock both locks to develop some fascinating spend conditions and smart contracts.

What is all this scripting stuff about?

When you “send” bitcoin to an address, say 1J7mdg5rbQyUHENYdx39WVWK7fsLpEoXZy. You’re not actually sending it anywhere.

This is just a convenient metaphor for us greybeards who grew up in a time when cheques were literally posted to their recipients.

In fact, what you are doing is locking up a UTXO with a script that effectively says, “Anyone who can prove that

they know the private key of the public key that when hashed gives you 1J7mdg5rbQyUHENYdx39WVWK7fsLpEoXZy, can have this bitcoin”.

Chapter 6 of Mastering Bitcoin dives into Bitcoin transactions and script in great detail, and I strongly recommend you read it.

It is this ability to assign funds to small pieces of code, rather than just an account number, that opens up so many potential uses for the world of programmable money.

The devil in the details

While the idea of TariScript seems pretty straightforward, getting it to a place where we could implement it securely took the Tari community over a year of iterating, refining, breaking, fixing and reviewing before we got to a place where we felt comfortable implementing the first version in code.

In this section, we’ll examine the TariScript scheme in detail. By the end of it, you should have a decent understanding of how TariScript actually works. And why it was such a long journey to get to this point.

Math ahead! This section also builds on the concepts we discussed in Mimblewimble - all the bits and Mimblewimble transactions.

The TariScript language

TariScript is inspired by and is based on Bitcoin script. Like its older cousin, TariScript is a stack-based language. It has strict size limits, and the instruction set is minimal.

This is for a good reason.

If you’ve followed this space at all, you’re no doubt jaded by the endless stream of headlines marking the various hacks, leaks, and oopsies stemming at least partly from the fact that smart contract platforms like Ethereum and Polygon offer Turing-complete scripting functionality.

tl;dr The more you let users do with your programmable money, the more bugs and vulnerabilities they will expose.

TariScript, on the other hand, tries to provide as much rope as we need to enable all of teh thingz, without letting you hang yourself. Specifically, we want to keep TariScript small enough that it is amenable to formal verification. At the very least, we’re leaving things open for TariScript scripts to be formally specified using methodology akin to Miniscript.

This also supports Tari’s philosophy of keeping the base layer compact while pushing large-scale contracts and digital assets platforms onto Layer 2. This is how Tari intends to scale to millions of users and digital assets without having the entire network come to a grinding halt every time a kitty breeds or an ape gets bored.

An example

For a complete list of Opcodes available in TariScript, see RFC-0202.

Let’s dive in with the one-sided payments example. The approach to one-sided payments is that Alice sends Tari to Bob using a shared secret in the UTXO commitment and a script locked to Bob’s private key. She does this without Bob getting involved at any point.

This means that both Alice and Bob have a key to unlock the first lock in the door. This situation is not ideal for Bob.

But Bob is mollified since only he has the key to the second lock, so ultimately, only he can spend these funds.

Let’s take a closer look at how the script resolution works.

When Alice creates the transaction, she looks up Bob’s public key (P_b) and hashes it to H_b.

She attaches the following script to the UTXO:

Dup HashBlake256 PushHash(H_b) EqualVerify

Alice signs the script along with some other housekeeping chores and broadcasts the transaction.

Later, when Bob comes online, his wallet scans the blockchain for UTXOs that have the script matching his public key hash.

Now to spend this UTXO, Bob needs the keys for both locks. He gets the key for the first (Mimblewimble) lock using Diffie-Hellmann key exchange with Alice’s public data in the transaction.

He also gets the value that Alice sent him by decrypting part of the bullet-proof.

He must make it so that the script executes and returns the second key, his public key, as a result.

When TariScript is validated, the script is run against an input stack provided by Bob. In this case,

Bob must provide a single element, his public key (P_b), as the script input.

Before the first instruction is executed, the stack2 and script look like this:

| Step | 0 |

|---|---|

| Script | Dup HashBlake256 PushHash(H_b) EqualVerify |

| Stack | P_b |

The script then runs, executing the instructions in order. If any instruction fails, the entire script fails. When the script completes, there must be a single item left on the stack, and that item must be a valid public key.

The first instruction is Dup, which takes the top item on the stack and duplicates it:

| Step | 1 (Dup) |

|---|---|

| Script | HashBlake256 PushHash(H_b) EqualVerify |

| Stack | P_b P_b |

The next instruction, HashBlake256 hashes the top stack item and pushes the result onto the stack. We’ll keep the same nomenclature that Alice used and note that the hash of P_b is H_b:

| Step | 2 (HashBlake256) |

|---|---|

| Script | PushHash(H_b) EqualVerify |

| Stack | H_b P_b |

Next, we have PushHash(H_b). As you might guess, this pushes the value H_b onto the stack:

| Step | 3(PushHash(H_b)) |

|---|---|

| Script | EqualVerify |

| Stack | H_b H_b P_b |

Finally, the last instruction, EqualVerify, removes and compares the top two stack items. If they’re equal, the script execution continues. If not, the script fails.

Assuming the hashes match, i.e. Bob provided a public key that matched the hash Alice provided, then the script completes successfully leaving Bob’s public key on the stack.

| Step | 4 - Complete |

|---|---|

| Script | |

| Stack | P_b |

The rules of TariScript say that the key for the second lock is the private key corresponding to P_b, which only Bob

knows. Bob proves that he knows this key by providing a signature in the transaction input data that says as much.

In this way, we’ve achieved one-sided payments in Tari. Incidentally, the script Alice used here is nearly identical to the most common Bitcoin script called “Pay to public-key hash”, or P2PKH. With TariScript, as with Bitcoin, there are many other scripts Alice could have used to lock the UTXO for Bob’s exclusive use.

“Pay to public key” (P2PK) is the simplest and would have been PushPublicKey(P_b). Bob would not need to provide any

input at all here because the stack would already have his public key after the single instruction completes.

RFC-0201 has several other more interesting examples that you might want to go explore.

Closing loopholes

So far, we’ve added a UTXO script and a consensus rule that requires that the result of the script is a public key for which the spender holds the private key.

You might not be surprised to know that these requirements aren’t enough to prevent shenanigans in Tari transactions.

Here are just some of the vulnerabilities present in the scheme at present:

Depending on the specifics of how Alice sends Tari to Bob and what the script is,

- Anyone can spend Bob’s funds by editing the script.

- Alice can lock Bob out of his funds by changing the script.

- Miners can edit parts of the transaction metadata without detection.

- Miners can take Bob’s funds by making the script disappear altogether.

- If Bob later sends funds to Charlie, Alice can collude with Charlie to steal funds from Bob.

- If there’s a really, really deep chain reorganisation, some nodes will have no way of knowing whether scripts were executed correctly and will have to trust whatever archival nodes tell them.

It took the Tari community almost a year to identify and resolve these vulnerabilities, so let’s take some time to have a look at them in more detail.

Malleability

The first three issues can be grouped together because they have the same underlying cause: malleability.

Put yourself in the shoes of a Tari node for a second. With the current naïve approach to TariScript, there’s no way for a node to know whether the script has been modified. A malicious intermediate node or a miner could have swapped out PushPublicKey(P_b) for PushPublicKey(P_c), and nobody would be any the wiser.

So the first thing we have to do is have Alice and Bob jointly commit to the extra data we’re adding to the transaction. For that matter, we can ask them to commit to some transaction metadata as well, which would close a malleability bug that’s been in Tari for some time. Nice! Two birds, one stone.

This commitment tells us, or anyone else, that the information captured in the UTXO is what both parties expect and intend. We can prove this by checking a joint signature attached to the UTXO, the metadata signature.

The metadata signature

Before TariScript, UTXO output features could be manipulated by miners without detection. The metadata signature closes that vulnerability and locks down all the data except for the range proof, which is already non-malleable.

The metadata signature is a joint, or aggregated, signature that is signed by the commitment (i.e. the combination of the spend key and value), which Bob the receiver usually knows, and the spender offset key, which Alice usually knows.

Notice that Bob signs with the commitment and not just the spend public key. If we did use just the spend public key, we would leak the value of most transactions.

The reason we would leak the values of transactions is a follows: Because $ C = k.G + v.H = P + V $, if we know $ P $, then $ V $ is trivial to calculate. Now with $ V = v.H $, we can pre-calculate a long list of $V$ for the most commonly used $v$ values (10, 1000, 10,000, 20,000 etc.) and have a simple lookup table to break confidentiality in the majority of Tari transactions.

As a result, we must use a twist on the Schnorr signature called a commitment signature. The details of commitment signatures are very straightforward and make an excellent topic for another TLU post.

The metadata signature signs the output features, the locking script, and commits to the commitment and spender public key. At last, changing anything in the UTXO will void this signature, and trying to replace the signature with a fraudulent one will be picked up by the kernel and spend key validation steps.

Input signatures

Another part of the transaction that’s vulnerable to malleability is the script’s input data that the spender may provide. We prevent tampering with this field by requiring the spender to commit to and sign the script and input data in the script signature (the same signature that unlocks the second lock on the UTXO).

Cut-through

In vanilla Mimblewimble, if Alice sends funds to Bob, who immediately spends that to Charlie (in a zero-confirmation transaction), then the block would look something like

+-------------------------+

| Header |

+-------------------------+

| Inputs Outputs |

| |

| A B |

| B C |

| |

+------------+------------+

Since B is identical from a mathematical perspective, they cancel each other out. Miners can take advantage of this

fact and remove B from the block altogether, in a process called cut-through:

+------------+------------+

| Header |

+-------------------------+

| Inputs Outputs |

| |

| A C |

| |

+-------------------------+

Once an output has been cut-through, it’s like it never existed. Any data associated with it is also gone forever. You might be able to deduce that something was cut-through if there are more kernels in the block than inputs, but generally speaking, cut-through is undetectable.

This poses a problem for TariScript because one of the two spending conditions lives in the UTXO– the script! Giving miners the power to make this disappear on a whim makes the entire concept unworkable.

Ultimately, the only way around this issue is to modify Mimblewimble to disallow cut-through completely.

Cutting cut-through

This is easier said than done.

Preventing cut-through requires us to chain input and outputs together to tell if a link has been removed. But the property of being able to jumble inputs and outputs together in an auto-coin-join is one of the core features of Mimblewimble itself!

What we need is a way to link inputs and outputs without explicitly linking them. See? Easier said than done.

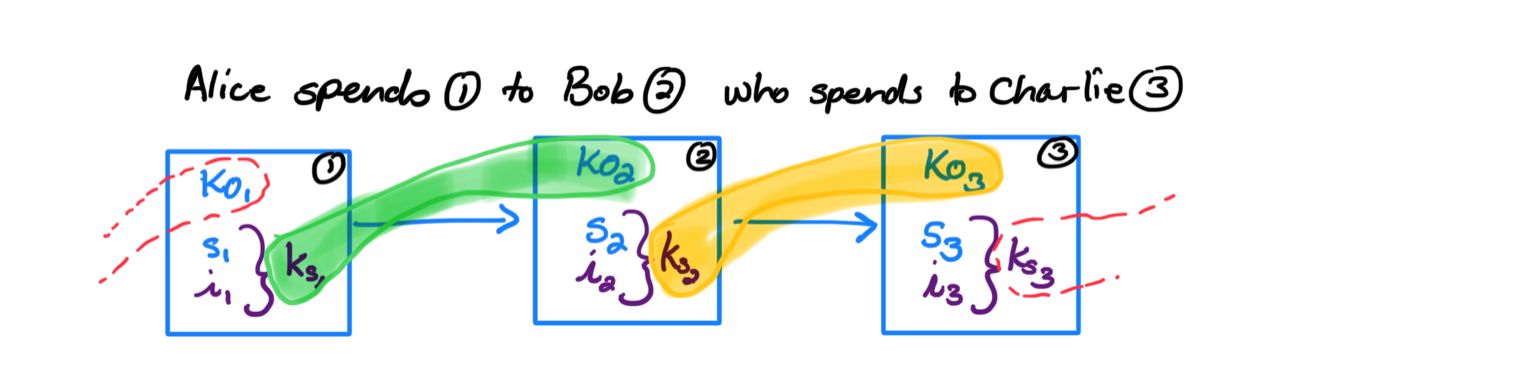

The way we achieve this is by introducing a script offset to Tari transactions. The script offset is an obfuscated link between something in the transaction inputs (the script key) and the outputs (the sender offset key), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Script offsets connect inputs and outputs without explicitly revealing their connection. Blue

terms are present in UTXOs. Purple terms are introduced when the outputs get spent.

Figure 1. Script offsets connect inputs and outputs without explicitly revealing their connection. Blue

terms are present in UTXOs. Purple terms are introduced when the outputs get spent.

It is an obfuscated link because the script offset is calculated using only secret values. For the transactions in Figure 1, the offsets are

\[\begin{align} \gamma_1 &= k_{s1} - k_{O1} \\ \gamma_2 &= k_{s2} - k_{O2} \end{align}\]Nodes can validate the transaction by checking the math on the public portions of the script offset, i.e. they check that

\[\begin{align} \gamma_1\cdot G &\stackrel?= K_{s1} - K_{O1} \\ \gamma_2\cdot G &\stackrel?= K_{s2} - K_{O2} \end{align}\]The second set of equations uses only public data that aggregates over the transactions in a block, the same way the accounting balance does. Therefore it’s impossible to tell which inputs are linked with which outputs. All you know is that no inputs or outputs are missing (i.e. cut-through).

Secondly, unlike commitments in the accounting balance, the offset equation uses different values from the outputs when they are created vs when they are spent. You can see this visually in Figure 1 in that the linkages are disjoint. This property means that the values do not cancel out when trying to perform cut-through. And so cut-through is disallowed by the script offset equation.

There’s one last bit of housekeeping to wrap this up. Tari now requires transactions to bundle the script offset along with the transaction, and block aggregators will sum all the offsets when building a new block and report a single aggregate script offset for the entire block. It’s a simple exercise to convince yourself that the aggregate equation, $ \gammaT \cdot G \stackrel?= \sum{K{sj}} - \sum{K_{Oi}} $ is all that’s required to prevent cut-through in blocks.

Replay attacks

The sender offset key also prevents replay attacks.

In the naïve implementation of TariScript, consider the following scenario:

- Alice sends a one-sided payment to Bob (Alice has the key for the first lock, because the commitment spend key is a shared secret).

- Bob later spends the UTXO by sending funds to Charlie. Bob has the key for the second lock, and presents the proof of such when constructing the transaction.

- Later, Alice sends another one-sided payment to Bob. Again, Alice has a key for the first lock.

- She then conspires with Charlie, to reuse the signature that Bob used when sending funds to Charlie. Even though they don’t have the key to the first lock, the input signature is sufficient to convince everyone that they do know it.

There are some steps one could take to make this attack more difficult, such as adding the commitment to the signature challenge. This still would not eliminate the attack, since Alice would then be careful to use the same shared secret and value (and thus the same commitment) in her second transaction to Bob.

Ultimately, there is no simple way to block this attack. For Tari, we decided to disallow duplicate excesses on transactions. This requires us to track an index of all transactions in Tari history, but look-ups are reasonably efficient and it stops the replay attacks.

Horizon attacks

Like other Mimblewimble protocols, Tari prunes its spent TXO set after some pruning horizon, typically a few hundred blocks. It can do this because spent outputs are not needed to carry out the overall accounting balance on the system. This is Mimblewimble’s primary scaling advantage over, say, Bitcoin.

Of course, when you prune a UTXO, you also prune its script and input data. This means that if there was a huge chain reorganisation beyond the pruning horizon, termed a horizon attack, then non-archival nodes would be unable to fully validate some transactions. They would have to find an archival node to replay the complete transcript between the chain split and the pruning horizon.

It is too much of a handicap to disable pruning in Tari, so the strategy is to mitigate rather than eliminate horizon attacks:

- Tari has a very long pruning horizon, several thousand blocks, to make the attack more expensive and less likely.

- Ensure that there is always a critical mass of archival nodes running.

- Users can protect their funds from horizon attacks by simply sending funds to themselves using a standard Mimblewimble transaction.

End credits

As you can see, the road from the initial idea of “Hey, let’s incorporate scripting into Mimblewimble” to the final product was an adventurous one. This feature is particularly gratifying because it was a complete team effort, with at least half a dozen contributors making vital additions. Special thanks go to @BlackwolfSA for breaking my first three or four iterations of this concept and first proposing the script key concept, @DavidBurkett for reviewing and coming up with the basic script offset idea and @Stringhandler, @SimianZa, @Bizzle and @HansieOdendaal for helping refine and polish TariScript into its final form.